The situation in Egypt gives much food for thought to us in Malaysia.

Many Egyptians who voted in the recently deposed President Mohamed Morsi last year and thus accepted the prospect of greater Islamisation of government rejected it after they saw more clearly the practical consequences of its implementation. On hindsight, electoral support for the promise of greater Islamisation of government seems to have been, in fact, a temporary proxy for the permanent desire for greater morality in public administration and justice in socio-economic outcomes. In Egypt, that promise had seemed particularly appealing on polling date about a year ago when juxtaposed against decades of nationalist maladministration.

Many Egyptians who voted in the recently deposed President Mohamed Morsi last year and thus accepted the prospect of greater Islamisation of government rejected it after they saw more clearly the practical consequences of its implementation. On hindsight, electoral support for the promise of greater Islamisation of government seems to have been, in fact, a temporary proxy for the permanent desire for greater morality in public administration and justice in socio-economic outcomes. In Egypt, that promise had seemed particularly appealing on polling date about a year ago when juxtaposed against decades of nationalist maladministration.

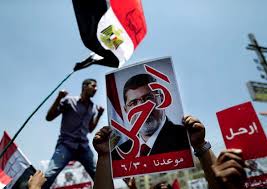

It is clear that Morsi, when in power on a slim electoral majority, had focused his energies on implementing greater Islamisation of government rather than greater efficiency of government. In the process, it became a Muslim Brotherhood (“Brotherhood”) campaign against not just remnants of the former Mubarak regime but seemingly, just about the rest of Egyptian society.

As a result, sufficient numbers of people who voted for Morsi protested to say that his way was not what they voted for. And they felt so strongly about it that they preferred not to wait the next few years to see if he would bring about greater morality in public administration and justice in socio-economic outcomes. They were urgently concerned that his style of administration would have brought ruination and despair before then. They observed that he relied more on the ideological reliability of a close circle of Brotherhood people rather the diverse talent of Egyptians.

Trusting the broad mass of Egyptians and the most talented amongst their professionals and intelligentsia would have been maximally possible had the unity and prosperity of the people been pursued rather than personal position, sectarian interests or religious vision. It was minimally possible for Morsi because his goal was to push through a Brotherhood agenda. It was an agenda that enough Egyptians, the vast majority of whom are Muslims, did not want. At the least, they did not want it with the same desire as solutions to the problems of daily living, which he did not deliver.

Morsi’s defenders ask: Why blame him for not solving the problems of the last sixty years in one year? The rejoinder to that should surely be: Why did he mess around with trying to consolidate power in Brotherhood circles using religion as the call card when there were urgent and practical issues awaiting resolution, many of which required respect for and co-operation from a diverse range of Egyptian institutions, companies and individuals? Morsi had a great opportunity to pursue justice and reconciliation. But he and his colleagues seemed to have been more consumed by power and retribution. Instead of staying close to the people and taking his wisdom from them, he sought to force abstract ideas on them.

Whilst Morsi failed to sufficiently respect democratic values, one must also decry his ouster by the military. It would have been better for Morsi to be rejected at the ballot box in the next elections by the people if that be their will rather than for him to be deposed undemocratically as he was. If the exigencies of the Egyptian situation that had built up in the last year could not wait for democratic change, the second best but nonetheless drastically worse solution would have been for the people and the people alone to clamour for change on the streets, as they have, but without the involvement of the military in the way that it did.

Whilst Morsi failed to sufficiently respect democratic values, one must also decry his ouster by the military. It would have been better for Morsi to be rejected at the ballot box in the next elections by the people if that be their will rather than for him to be deposed undemocratically as he was. If the exigencies of the Egyptian situation that had built up in the last year could not wait for democratic change, the second best but nonetheless drastically worse solution would have been for the people and the people alone to clamour for change on the streets, as they have, but without the involvement of the military in the way that it did.

The military’s involvement in the politics of the people is a setback for Egypt. The job of the military and the armed instruments of the state in a tumultuous situation of internal discord should be to protect the state and guard over the safety of the people and their property. As ultimate authority becomes grey and fluid, they must show restraint and thus own the moral authority to ask politicians to show restraint. As it 2 was, the Egyptian military showed its hand openly to effect change. It delivered a knock down punch that has left some external bleeding, broke the bones of the Morsi government and caused severe trauma inside the body politic of Egypt. Now, it is not easy to discern if the military had merely supported the will of the majority of Egyptians or it had connived to support a minority against the majority. It also unwittingly facilitated the allegation that deposing Morsi undemocratically was the act of secularists against Islam. This traumatic event will affect the future development of Egypt for the worse. An assault on a democratically elected government necessarily undermines the development of democracy, which is the most important source of resilience of any modern nation state.

The salvation of Egypt lies in greater democracy. In the next elections due later this year, the Brotherhood should have the opportunity to present its credentials to the Egyptian people again. However, this time, it will face the disadvantage of being judged on Morsi’s woeful performance in office until his ouster and much more organised competition from other contestants, including possibly Mubarak remnants. For the people of Egypt, the availability of choice suggests that they still have the opportunity to progress politically. Egyptians who wish for both Islam and democracy should embrace politics that champion freedom and the rule of law. On the evidence to date, Islam can thrive in a democratic state more than democracy can thrive in an Islamic state.

To the business class of Egypt, the message should be this: The military does not represent modernity and efficiency any more than Islamists represent morality and justice. Peace-loving citizens going about their daily work and lives, with abiding faith in God, will naturally seek morality and justice. They will also find ways to organize themselves efficiently and seek modernity in a comprehensive way. It is with the people that the business class should align with.

The above observations are about Egypt but it is meaningful to relate the developments there to the situation in Malaysia. There are sufficient similarities in the underlying dynamics which make the situation in Egypt worthy of careful study by politicians on both sides of the political divide in Malaysia.

We would do well to see that any attempt at imposing Islamic theocratic rule is fraught with the risk of rejection by a large proportion, possibly a majority, of Muslims themselves. Even if rejection does not come from the majority of Muslims, it will likely come from a substantial minority of them. In any case, it would be enough to open another fissure in our society. Non-Muslims will unavoidably be drawn into such a situation because we are all part of an interwoven social, political and economic fabric.

In the next general elections, the administrative fiascos of GE-13 should not be repeated. An incumbent government that survives a robust but fair contest strengthens its own legitimacy. Should there be a change in government through the ballot box, the will of the people must be respected and a smooth and respectful transition of power should follow with much dignity and decorum. The civil service, the military, the police, judiciary and all other national institutions should remain neutral and in the service of the country. Only if we develop a democratic tradition in this country and respect it can we hope to become a developed country. Otherwise, we will end up creating for ourselves the kind of situation that we see in Egypt today. It is not a pretty sight.

Harold Kong

6 July 2013