Prime Minister Najib Razak’s announcement of a minimum wage requirement for the private sector has been met with outrage from pro-business Malaysians.

Prime Minister Najib Razak’s announcement of a minimum wage requirement for the private sector has been met with outrage from pro-business Malaysians.

Their argument, in short, is that there should be no minimum wage at all. A minimum-wage policy will only increase business costs, which will only lead to inflation. Companies will also be reluctant to hire more workers as a result.

Ideas director Wan Saiful Wan Jan even went so far as to say that the new minimum wage policy will eventually compel workers to turn to the black market in search for employment. He thus describes the policy as nothing short of an “intervention” in the name of “populism” — a clear breach of the natural process of growth that a truly free market would assure for everyone.

What has changed?

Contrary to capitalist fears, the minimum wage will do little to alleviate the standard of life for Malaysia’s working poor. If anything, the rate of RM900 per month for peninsular Malaysia and RM800 for Sarawak, Sabah and Labuan only appear “populist” because Malaysia never had a minimum wage policy before.

The problem begins with the fact that the rate is unrealistic. According to the Ministry of Human Resources, 34 per cent of Malaysian workers earn less than RM700 per month.

According to the Malaysian Trades Union Congress, this is especially true of the five manufacturing sub-sectors, i.e. electric and electronics, furniture, plastics, gloves and textiles whereby basic wages average to RM626.76 per month. It is also widely understood that many plantation workers in Malaysia are still being paid around RM400 per month.

But what is the poverty line, exactly? As of 2007, the official household poverty line for West Malaysia is RM720. That is to cover basic household needs, which is supposed to include food, clothing, rent, transportation and communication. In other words, it expresses an amount enough for a household to survive.

But does that number tell the full story of poverty and survival? To have a better view of this, let’s imagine a poor family of four in the Klang Valley with rather conservative spending habits. Their income will have to go to rent (RM400), groceries (RM300), school expenses (RM200), motorbike (RM150) utilities and phone bills (RM100) and savings (RM200). This is assuming that both parents are fit enough to work full time and that they do not have more children in the process.

The total comes up to RM1,350.

The family will “survive”, although in the most very basic sense of the word, with little time for family, community or leisure, or even one’s self.

All this is to say that, the minimum wage policy of RM900 per month will lead to little to no real improvement to the lives of those who need it the most. It does not even begin to address the severity of poverty in Malaysia, much less secure their fundamental needs as human beings.

Why a minimum wage?

Anyway, the outrage against the minimum wage policy obscures the fundamental question that’s not been asked enough, and that is why a minimum wage is even needed to begin with.

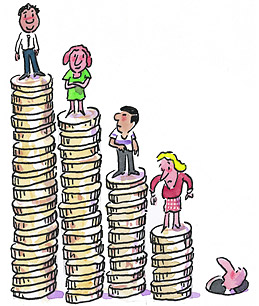

In the first place, there is the obvious principle that wealth should be shared with the people who help produce it. This is a simple matter of workers’ rights. The worker has a right to the wealth that was produced as a direct result of his or her efforts. This is also democratic; more often than not, there are more workers than bosses in any given bank, firm or corporation.

No talk of rights, of course will, appear in the discourse, given that the interest of business first and foremost is profit, not welfare. As is typically the case in modern capitalist societies, business interests coincide with that of the government. The prime minister himself said that a rate higher than RM900 “can be detrimental to the nation’s economy, labour market and foreign investment into Malaysia.”

The logic that such excuses often overlook is that a decent minimum wage will also extend purchasing power, as it will lead to more people having more money, thus encouraging consumption and growth. More money in the hands of more people will let them buy more things.

The increase in demand for products from workers who make better wages will increase more jobs. This is one step forward to dealing with the common complaint from foreign investors that Malaysia does not have a large enough domestic market.

At any rate, the reality is that the ones who would be most offended by the minimum wage requirement are those capitalists who want to claim as much profit as possible, away from the reaches of their workers. The libertarian will argue that this is fair and square since it was his capital, and thus as much profit should be his and his only — to which we can simply ask: How is that self-centredness not detrimental to the nation’s economy?

Now we shall consider Wan Saiful Wan Jan’s bourgeois fear of poor people doing evil things in an underground economy. To begin with no one would feel the need to search for work in a black market economy if they made decent wages.

Put as simply as possible, increasing the minimum wage to a level that secures the basic needs of a household will make it less likely for people to want to search for subsistence elsewhere. They would also have more time for community and family, in other words, more time to instil the right values to their children.

Let’s not forget that capitalists — especially those who really do not want any government interference into their businesses — thrive in underground economies as well.

Another classist fear that has emerged in these debates is the supposition that workers will be less motivated to work once they know that they will be secured a certain amount of wages every month. This is simply illogical, not to mention prejudiced — a myth rooted to the rich’s assumption that they deserve their wealth more than others because they somehow “worked hard”.

For one, a decent minimum wage requirement is not a guarantee of employment.

Secondly, the presupposition that minimum wages decrease productivity is just false. Studies upon studies have shown that workers are motivated to work well when they earn decent wages that secure their need of subsistence. In one research conducted by the Economic Policy Institute in Washington D.C., economist Jeff Chapman confirmed that “the economic evidence is pretty clear that if you get paid enough and have a good attitude about working somewhere, then you are less likely to not show up for work and not shirk your duties.”

Having a happy staff will also reduce turnover, which is good for business since keeping workers is always cheaper than constantly having to find and train new ones. Employers will also not be placed in a competitive disadvantage, since with minimum wage laws enforced, all businesses would have to abide by it. A decent minimum wage, in other words, increases productivity.

Lastly, when the virtues and requirement of real decent wages are finally understood and met by the company, the libertarian will also have no need to fear what they’ve always touted as the worst thing on earth, which is big government.

Moving Forward

Given the meagreness of the current minimum wage, and the faulty arguments against it from capitalists, the government must show that the new policy is not just a measure of token pseudo-populism.

For this, it must face Malaysian reality and increase the minimum wage and ensure its enforcement. In this, Parti Sosialis Malaysia’s recommendation of RM1,500 per month appears as a better start, all things considered.

Whatever disagreements that will ensue in subsequent debates on this matter should not lose sight of the fact that income, while not inaccurate, remains the most superficial way of understanding poverty. The capabilities approach, for example, has a more comprehensive take on poverty alleviation, factoring into account overall quality of life beyond the figures recorded by a nation’s GDP or GNP.

Martha Nussbaum’s version of the approach, for example, includes bodily integrity, emotional well being, environmental safety, social life and play, among other factors, as also part of what it means to be human. By this, wealth and poverty should not simply be understood in terms of income, but the life that is lived as a result.

This approach, thus, views poverty as the state of affairs that deprives the individual from opportunities to exercise our human capabilities, the very state of affairs that tend to prevail in most capitalist societies that do not take into account the welfare of the poor and the working class — there’s no time to ponder too much about what it means to be human, when we haste to bend over backwards to ensure that foreign investors are always happier than our own fellow citizens.

“It is but equity… that they who feed, clothe and lodge the whole body of the people, should have such a share of the produce of their own labour as to be themselves tolerably well fed, clothed and lodged.” ~ Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, 1776.

(This article was also published by Harakah Daily.)