Ahmad N. Amir, Abdi O. Shuriye & Jamal I. Daoud || 20 December 2020

ABSTRACT

Muhammad Abduh had a remarkably profound and lasting impact in Southeast Asia. His reformist ideas had strong repercussions in the political and social landscape of the region. They were readily adopted by major Islamic movements, notably Muhammadiyah, al-Irshad and Persatuan Islam (Persis). Abduh’s Tafsir al-Manar deeply influenced Tafsir al-Azhar, Tafsir al-Qur’an al-Karim, Tafsir al-Qur’an al-Madjid (Tafsir al-Nur), Tafsir al-Quran al-Hakim, Tafsir al-Misbah, and Tafsir al-Furqan. His Majallat al-Manar inspired reform-oriented scholarship evident in journals such as al-Munir, al-Imam, Saudara, al-Ikhwan, al-Dhakhirah al-Islamiyah and Seruan Azhar. This paper surveys Abduh’s extensive influence, especially his impact on Islamic reform and renewal (islah and tajdid) in the Malay Archipelago.

Key words: Muhammad Abduh • Southeast Asia • intellectual tradition • modern thought • Islamic reform

INTRODUCTION

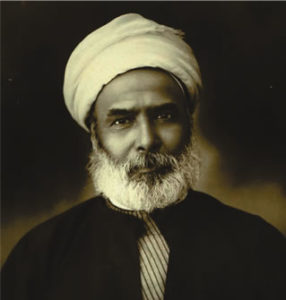

The need for reform initiated by Muhammad Abduh in Egypt had a phenomenal impact in Southeast Asia. Many great scholars and reformists branded as Kaum Muda (the young Turks) were deeply influenced by his ideas and aspirations. Notable among them are Haji Abdul Karim Amrullah (Haji Rasul) (1879-1945), Haji Abdul Malik bin Abdul Karim Amrullah (1908-1981) (Padang Panjang, West Sumatera), Kiyai Haji Ahmad Dahlan (1868-1923) (Yogyakarta), Abdul Halim Hassan, Zainal Arifin Abbas and Abdur Rahim Haithami (North Sumatra), Syeikh Ahmad Muhammad Surkati (1875-1943) (Betawi), T.M. Hasbi ash-Shiddiqi (1904-1975) (Acheh), Ahmad Hassan (1887-1958) (Bandung), K.H. Moenawar Chalil (1908-1961) (Kendal, Central Java), Quraish Shihab (1944-) (Jakarta), Zainal Abidin Ahmad (Za‘ba)(1895-1973) (Kuala Pilah, Negeri Sembilan), Syeikh Muhammad Tahir Jalaluddin al-Falaki (1869-1956) (Minangkabau), Syed Sheikh al-Hadi (1867-1934) (Pulau Pinang), Haji Abu Bakar al-Ashaari (1904-1970) (Pulau Pinang) Dr Burhanuddin al-Helmi (1911-1969) (Taiping, Perak) and Mustafa Abdul Rahman (1918-1968) (Gunung Semanggol, Perak), among others. Abduh’s indelible legacy in the Malay-Indonesian world is evident in the scholarship he inspired among reform-oriented scholars in the form of tafsir, journals, press, magazines, schools, religious movements and institutions that flourished in the 19th and 20th century.

The need for reform initiated by Muhammad Abduh in Egypt had a phenomenal impact in Southeast Asia. Many great scholars and reformists branded as Kaum Muda (the young Turks) were deeply influenced by his ideas and aspirations. Notable among them are Haji Abdul Karim Amrullah (Haji Rasul) (1879-1945), Haji Abdul Malik bin Abdul Karim Amrullah (1908-1981) (Padang Panjang, West Sumatera), Kiyai Haji Ahmad Dahlan (1868-1923) (Yogyakarta), Abdul Halim Hassan, Zainal Arifin Abbas and Abdur Rahim Haithami (North Sumatra), Syeikh Ahmad Muhammad Surkati (1875-1943) (Betawi), T.M. Hasbi ash-Shiddiqi (1904-1975) (Acheh), Ahmad Hassan (1887-1958) (Bandung), K.H. Moenawar Chalil (1908-1961) (Kendal, Central Java), Quraish Shihab (1944-) (Jakarta), Zainal Abidin Ahmad (Za‘ba)(1895-1973) (Kuala Pilah, Negeri Sembilan), Syeikh Muhammad Tahir Jalaluddin al-Falaki (1869-1956) (Minangkabau), Syed Sheikh al-Hadi (1867-1934) (Pulau Pinang), Haji Abu Bakar al-Ashaari (1904-1970) (Pulau Pinang) Dr Burhanuddin al-Helmi (1911-1969) (Taiping, Perak) and Mustafa Abdul Rahman (1918-1968) (Gunung Semanggol, Perak), among others. Abduh’s indelible legacy in the Malay-Indonesian world is evident in the scholarship he inspired among reform-oriented scholars in the form of tafsir, journals, press, magazines, schools, religious movements and institutions that flourished in the 19th and 20th century.

THE SPREAD OF ABDUH’S IDEAS IN MALAY ARCHIPELAGO

Muhammad Abduh’s ideas began to spread in the 19th-20th century through scholars trained at Al-Azhar who brought back Islamic reform (tajdid) into the Malay-Indonesian world. The strong connection established with the al-Manar‘s circle in Egypt helped to spread Abduh’s progressive views. This was instrumental in sowing the seeds of the reformist movement in the Malay-Indonesian world, as stated by Mohd Shuhaimi Ishak in his dissertation on the impact of Abduh’s rationality on Harun Nasution’s worldviews: “The birth of the modernist reformist Pan-Islamism advocated by al-Afghani and ‘Abduh, attracted a vast audience among young students. Cairo, during the colonial times and particularly in the 1920s, provided a fertile ground for the Southeast Asian students.” [42].

The network established between the Middle East and the Malay Archipelago firmly established Abduh’s influence in the region, as acknowledged by Azyumardi Azra in his study of the transmission of Abduh’s reformism in the region: “The increasing contact between Muslims from the Middle East and the Malay Archipelago was due to many factors, including the rapid development in navigation technologies, the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, the monetization of the colonial economy, which benefitted certain classes in the colony and the greater global community of populations” [11].

Many factors contributed to establish the contacts between Malay world and the Middle East, mainly the learning activity in Cairo and the invention of printing machines [20]. Haramayn was “the largest gathering point of Muslims from all over the world, where ulama, Sufis, rulers, philosophers, poets and historians met and exchanged information” [37]. Cairo was the cornerstone of tradition and the epicentre of cultural and religious movements, as confirmed by Zakaria Mohieddin, former Prime Minister of Egypt: “Cairo has been and will always be a citadel of faith and a center of Islamic activity for the general welfare of the people” [49]. Al-Manar’s significant contact with Malay-Indonesian reformists unleashed a strong wave of reform, as asserted by Michael Laffan: “With the expansion of the resident community of Indonesians in Egypt, the Cairene body has now come to represent far more than the revivalist scripturalism laid out by Muhammad Abduh” [39]. It had developed significant impact and inspired dynamic connection with the Malay-Indonesian world and “through this relationship, ideas on Islamic reformation that were advocated by Egyptian reformists were absorbed and diffused amongst the Muslim society in this region” [24].

Many factors contributed to establish the contacts between Malay world and the Middle East, mainly the learning activity in Cairo and the invention of printing machines [20]. Haramayn was “the largest gathering point of Muslims from all over the world, where ulama, Sufis, rulers, philosophers, poets and historians met and exchanged information” [37]. Cairo was the cornerstone of tradition and the epicentre of cultural and religious movements, as confirmed by Zakaria Mohieddin, former Prime Minister of Egypt: “Cairo has been and will always be a citadel of faith and a center of Islamic activity for the general welfare of the people” [49]. Al-Manar’s significant contact with Malay-Indonesian reformists unleashed a strong wave of reform, as asserted by Michael Laffan: “With the expansion of the resident community of Indonesians in Egypt, the Cairene body has now come to represent far more than the revivalist scripturalism laid out by Muhammad Abduh” [39]. It had developed significant impact and inspired dynamic connection with the Malay-Indonesian world and “through this relationship, ideas on Islamic reformation that were advocated by Egyptian reformists were absorbed and diffused amongst the Muslim society in this region” [24].

In early 20th century, the wide circulation of “islah-oriented” journals, magazines and newspapers such as al-Imam (Singapore), al-Munir (West Sumatera), al-Huda, al-Iqbal (Java), al-Mir’ah al-Muhammadiyah (Yogyakarta), al-Tadhkira al-Islamiyah, Pembela Islam (Bandung), al-Irsyad (Pekalongan), Tunas Melayu, al-Ikhwan and Saudara and other influential works in Malaya contributed to extend Abduh’s influence and sparked an unprecedented reform movement for Islamic revival in the Malay world.

Abduh’s legacy attracted many local scholars from various persuasion and school of thoughts. This was reflected in the request that was directed to al-Manar “which emanates from three groups: Southeast Asian students in the Middle East, Arabs living in Southeast Asia and indigenous Southeast Asian readers of al-Manar” and primarily related to themes on “Islam and modernity, religious practices and aspirations for religious reform” [35]. The principal question came in 1930 from Shaykh Muhammad Basyuni b. ‘Imran (1885-1981) from Sambas, West Kalimantan, and was addressed to Shakib Arsalan (1869-1946). He had two important queries; he asked why Muslims (particularly in the Malay world) decline and why non-Muslims advance. The response by Arsalan was published in a series of articles in al-Manar and later compiled in a work entitled Li madha ta’akhkhar al-Muslimun wa limadha taqaddam ghayruhum? (Why are Muslims in decline while others progress?) This dialogue was thoroughly investigated by Juta Bluhm in her article that looks into the contact between Cairo and the Malay world; it pointed out that “there was interaction between al-Manar readers in the Malay world and the editors of the periodicals. In this regard, Malay individuals from Malaya, Kalimantan, Sumatra and other parts of the region wrote to those editors seeking advice and offering opinions on a broad range of theological questions, economic and environmental problems, technological advances, issues of current political concern such as patriotism and a range of other matters…indeed, during the period of its publication (1898-1936), al-Manar published 26 articles and some 135 requests for legal opinions from the Malay-speaking world” [13].

ABDUH’S IMPACT ON TAFSIR LITERATURE

Tafsir al-Manar, dictated by Muhammad Abduh and later published by Muhammad Rashid Rida in his periodical al-Manar, was highly influential in the Malay Archipelago and had extensive impact on tafsir produced in the 20th century. It showcased an important methodology of Qur’anic exegesis that celebrated the power of reason, besides encouraging critical understanding and definitive ijtihad (independent reasoning). The volume featured commentaries based on a systematic exposition of rational principles and a scientific framework, which kept it free from the shackles of classical ideology rooted in tafsir. Echoing the principles of Abduh, Muhammad Asad stressed this point in his voluminous work The Message of the Qur’an: “The spirit of the Qur’an could not be correctly understood if we read it merely in the light of later ideological developments, losing sight of its original purport and meaning. In actual fact we are bent to become intellectual prisoners of others who were themselves prisoners of the past and had little to contribute to the resurgence of Islam in the modern world” [45].

Tafsir al-Manar, dictated by Muhammad Abduh and later published by Muhammad Rashid Rida in his periodical al-Manar, was highly influential in the Malay Archipelago and had extensive impact on tafsir produced in the 20th century. It showcased an important methodology of Qur’anic exegesis that celebrated the power of reason, besides encouraging critical understanding and definitive ijtihad (independent reasoning). The volume featured commentaries based on a systematic exposition of rational principles and a scientific framework, which kept it free from the shackles of classical ideology rooted in tafsir. Echoing the principles of Abduh, Muhammad Asad stressed this point in his voluminous work The Message of the Qur’an: “The spirit of the Qur’an could not be correctly understood if we read it merely in the light of later ideological developments, losing sight of its original purport and meaning. In actual fact we are bent to become intellectual prisoners of others who were themselves prisoners of the past and had little to contribute to the resurgence of Islam in the modern world” [45].

Tafsir al-Manar also referred to classical works from al-Tabari to al-Alusi as its primary sources while employing high level of ijtihad and sound reason to understand the text. It was hailed as the greatest work of tafsir in the 20th century. Indeed, it ushered a modern approach of exegesis in the continent, while becoming the primary reference of tafsir in the Malay archipelago. This is mentioned by M Abdullah in his analysis of the key influence of Egyptian reformists on the works of tafsir manuscript in the Malay archipelago: “The trend of writing tafsir (exegesis) manuscripts in the Malay Archipelago during the first part of the 20th century was very much influenced by the Islamic reformation in Egypt initiated by Syaykh Muhammad ‘Abduh (1849-1905), which was later expanded by his disciples such as Sayyid Muhammad Rasyid Rida (1865-1935), Syaykh Mustafa al-Maraghi (1881-1945) and other scholars with similar orientation.” [38].

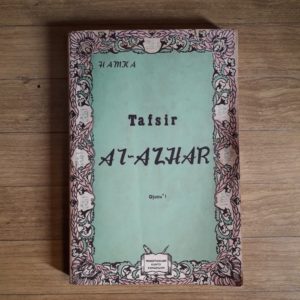

Tafsir al-Azhar: Tafsir al-Azhar was a major work of tafsir by Shaykh Haji Abdul Malik b. Abdul Karim Amrullah (Hamka) that played a crucial role in realizing the aspiration for reform and renewal in Indonesia. It was compiled from Hamka’s lecture on the commentary of the Qur’an delivered at Al-Azhar Mosque, Kebayoran Baru, Jakarta in the kulliyyah subuh (seasonal class after dawn). Since 1959, the commentary was published in Gema Islam, an influential periodical which profoundly reflected the idealism of Muhammad Abduh, the “leading exponent of modern Islam in Egypt”, [27], as indicated in the style and approach of the tafsir. The largest part of the tafsir from surah al-Mu’minun (the Believers) to al-Baqarah (the Heifer) was completed in jail (27 January 1964-21 January 1967) when Hamka was falsely charged and accused of plotting to topple the democratic government. Dedicated to young Muslims with an inadequate knowledge of Arabic who were trying to understand the Qur’an, the Tafsir served as da‘wah materials for leading mubaligh and cadre of Muhammadiyah.

Released in 1961, the Tafsir clearly portrayed the impact of Abduh’s reformism in its exposition, as remarked by Milhan Yusuf in his thesis “Hamka’s Method of Interpreting the Legal Verses of the Qur’an: a Study of his Tafsir al-Azhar”: “Having been influenced by the Muslim reformist ideas championed by Muhammad ‘Abduh and his colleagues, Hamka attempted to disseminate and ameliorate the reform ideas in his country, Indonesia, through the means available to him, that is by preaching and writing” [69]. Milhan also described the principal influence of Abduh’s rational ideology and critical philosophy of jurisprudence that impacted the tafsir: “Hamka’s conception of the law portrays his challenge and struggle towards the abolishment of taqlid (uncritical acceptance of the decisions made by Muslim predecessors) and the implementation of ijtihad (personal opinion)” [69]. Muhammad Abduh’s phenomenal influence is acknowledged in the introduction of Tafsir Al-Azhar: “A very interesting and captivating commentary to be an example for the commentator is Tafsir al-Manar, penned by Sayyid Rashid Redha, based on the teachings outlined by his teacher Imam Muhammad Abduh. His Tafsir, besides interpreting science pertaining to religion, comprising hadith, jurisprudence and history and others, also synchronize the verses with the current development of politics and social, corresponding to the time the Tafsir was composed and crafted” [27]. Hamka had been exposed to the reform tradition brought from the Middle East since his early years, as evidenced in his keynote address on the occasion of receiving a honorary doctorate from al-Azhar University: “I admit that I never learned, either in al-Azhar or at Cairo University, but my intimate relationship with Egypt had long been rooted, since I managed to read Arabic books, especially of Shaykh Muhammad Abduh and Sayyid Rashid Ridha” [26].

Released in 1961, the Tafsir clearly portrayed the impact of Abduh’s reformism in its exposition, as remarked by Milhan Yusuf in his thesis “Hamka’s Method of Interpreting the Legal Verses of the Qur’an: a Study of his Tafsir al-Azhar”: “Having been influenced by the Muslim reformist ideas championed by Muhammad ‘Abduh and his colleagues, Hamka attempted to disseminate and ameliorate the reform ideas in his country, Indonesia, through the means available to him, that is by preaching and writing” [69]. Milhan also described the principal influence of Abduh’s rational ideology and critical philosophy of jurisprudence that impacted the tafsir: “Hamka’s conception of the law portrays his challenge and struggle towards the abolishment of taqlid (uncritical acceptance of the decisions made by Muslim predecessors) and the implementation of ijtihad (personal opinion)” [69]. Muhammad Abduh’s phenomenal influence is acknowledged in the introduction of Tafsir Al-Azhar: “A very interesting and captivating commentary to be an example for the commentator is Tafsir al-Manar, penned by Sayyid Rashid Redha, based on the teachings outlined by his teacher Imam Muhammad Abduh. His Tafsir, besides interpreting science pertaining to religion, comprising hadith, jurisprudence and history and others, also synchronize the verses with the current development of politics and social, corresponding to the time the Tafsir was composed and crafted” [27]. Hamka had been exposed to the reform tradition brought from the Middle East since his early years, as evidenced in his keynote address on the occasion of receiving a honorary doctorate from al-Azhar University: “I admit that I never learned, either in al-Azhar or at Cairo University, but my intimate relationship with Egypt had long been rooted, since I managed to read Arabic books, especially of Shaykh Muhammad Abduh and Sayyid Rashid Ridha” [26].

The approach of Tafsir al-Azhar was primarily based on the critical framework of commentary and rational interpretation outlined by Muhammad Abduh in Tafsir al-Manar, which defended the supremacy of reason and upheld the principle of ijtihad based on maslahah (general welfare), as argued by Ahmad Farouk Musa in his article “Muhammad Asad’s Tafsir: Reverberating Abduh’s Principles”: “The third principle of Abduh is asserting a claim to “renewed interpretation” (ijtihad) of Islamic law based on the requirements of “social justice” (maslahah) of his own era. According to Abduh, where there seems to be a contradiction between “texts” (nas) and “social justice” (maslahah), then social justice must be given precedence. Abduh supports the principle based on the notion that Islamic law was revealed to serve, inter alia, human welfare. Hence, all matters which preserve the well-being of the society are in-line with the objectives of the sharia and, therefore, should be pursued and legally recognized. Abduh believed that independent thinking (ijtihad) would enlarge the scope of knowledge because most of the aspects of human welfare (mu‘amalat) can be further elaborated with the use of reason (‘aql)”. Tafsir al-Azhar radically challenged the status quo and emphasized the need to transform the worldview and reclaim the authentic values of religion as promulgated by the “salafi “ Hamka, who was a reformer, also interpreted verses of the Qur’an in the context of his reform ideas in which bid‘a (innovations in the realm of religion), and superstition were the main targets[65]. This clearly resonates Abduh’s aspiration and struggle to advocate Islamic modernism, by outlining an approach to “return” to a pure understanding of Islam by interpreting the Qur’an and the sunna through the use of independent and rational investigation (ijtihad) above the allegedly blind reliance (taqlid) upon the opinions of the medieval jurists” [39].

The Tafsir also developed a scientific methodology of exegesis which emphasized the central role of ‘aql (reason) and its high place in textual exegesis, as stated by Rosnani Hashim in her article “Hamka, Intellectual and Social Transformation of the Malay World”: “A visible concern in his tafsir was the issue of ‘aql (reason), rationality and reason. This concern is definitely related to his support of the reformist movement and the neglect of Muslims over the use of reason and their dependence over taqlid. He argues that it is ‘aql that enables man to distinguish between good and evil and to appreciate God’s creation around him. The use of ‘aql is essential in examining ambiguity and the meaning of the Qur’an” [56]. The Tafsir also portrayed the political and social life in Indonesia as discussed by Wan Sabri in his thesis “Hamka’s Tafsir al-Azhar: Qur’anic Exegesis as a Mirror of Social Change” that analyses the significance of the tafsir as a reflection of the socio-political experience of Indonesia: “Tafsir al-Azhar was a mirror of social change: pre-independence and post-independence Indonesia. All such issues were used to contextualize the meanings of verses of the Qur’an so that they were understood and related better to the Malay-Indonesian people” [65].

Tafsir al-Qur’an al-Karim: Tafsir al-Qur’an al-Karim is a monumental work of exegesis that fundamentally derived its interpretation and commentary from Tafsir al-Manar. The work was essentially based on Tafsir al-Manar for its method and ideas. It was the fruit of the painstaking efforts of Abdul Halim Hassan (1901-1969) and his students Zainal Arifin Abbas (1912-1977) and Abdur Rahim Haitami (1910-1948), a remarkable attempt to produce a scientific and modern exegesis that profoundly extended al-Manar’s scientific approach and rational method of tafsir. It was crafted according to the manhaj al-adabi ijtima‘i (cultural and social method) that reflected the socio-political setting of the time. The commentary employed a hermeneutic and inter-textual approach that mirrored the extensive principle of hermeneutic and rational framework developed in al-Manar.

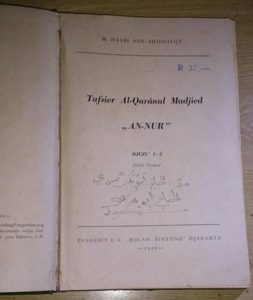

Tafsir al-Qur’an al-Madjied (Tafsir al-Nur): Tafsir al-Qur’an al-Madjied, famously known as Tafsir al-Nur, is a comprehensive work of Qur’anic exegesis by Teungku Mohammad Hasbi ash-Shieddiqy (1904-1975) that explicated the ideas of reform advocated by Muhammad Abduh and Muhammad Rashid Rida in Tafsir al-Manar. It strongly advocated Abduh’s major aspirations for reform (islah) and renewal (tajdid); it derived its commentary from Abduh’s major works such as Tafsir al-Manar, Tafsir Juz ‘Amma, Risalat al-Tauhid and al-‘Urwa al-Wuthqa (the firmest bond). Ash- Shieddiqy also published Tafsir al-Bayan which is largely based on Tafsir al-Maraghi and Tafsir al-Manar and were instrumental in realizing social, political and religious reform in Indonesia.

Tafsir al-Qur’an al-Madjied (Tafsir al-Nur): Tafsir al-Qur’an al-Madjied, famously known as Tafsir al-Nur, is a comprehensive work of Qur’anic exegesis by Teungku Mohammad Hasbi ash-Shieddiqy (1904-1975) that explicated the ideas of reform advocated by Muhammad Abduh and Muhammad Rashid Rida in Tafsir al-Manar. It strongly advocated Abduh’s major aspirations for reform (islah) and renewal (tajdid); it derived its commentary from Abduh’s major works such as Tafsir al-Manar, Tafsir Juz ‘Amma, Risalat al-Tauhid and al-‘Urwa al-Wuthqa (the firmest bond). Ash- Shieddiqy also published Tafsir al-Bayan which is largely based on Tafsir al-Maraghi and Tafsir al-Manar and were instrumental in realizing social, political and religious reform in Indonesia.

Tafsir al-Qur’an al-Hakim: Tafsir al-Qur’an al-Hakim, by Shaykh Mustafa ‘Abd al-Rahman Mahmud (1918-1968), is a highly influential work that briefly summarized Tafsir al-Manar. It followed Abduh’s method in explaining the Qur’an rationally and scientifically. It was a massive work that pioneered a modern and nuanced style of exegesis that contextualized its meaning and objective into its contemporary milieu. Shaykh Mustafa was so influenced by the scientific method applied in Tafsir al-Manar that he meticulously summarized it into Malay, as demonstrated from its title Tafsir al-Qur’an al-Hakim, the original name of Tafsir al-Manar. In her scrupulous analysis of the influence of Tafsir al-Manar on Tafsir al-Qur’an al-Hakim, Nadzirah Mohd emphasized this point: “The exegetical work of Shaykh Mustafa is an example of this influence by al-Manar school of thought in the Malay world. In fact, even the title of the tafsir i.e., Tafsir al-Qur’an al-Hakim wass the exact original title of the work by Shaykh Muhammad Rashid Ridha, which is now better known as Tafsir al-Manar…in his work, he relies greatly on Tafsir al- Manar and Tafsir al-Maraghi…it seems that Shaykh Mustafa has succeeded in implanting the reformist ideas of al-Manar into the Malay world, not only the religious and social reform but, most importantly, in presenting a new style of exegetical writing contextualized to the Malay world.”[48].

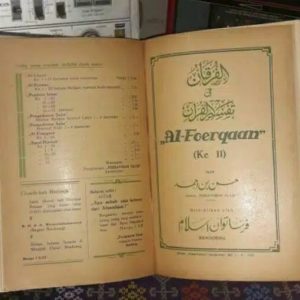

Tafsir al-Furqan: Kitab al-Furqan fi Tafsir al-Qur’an or al-Furqan Tafsir al-Qur’an is an acclaimed work by A. Hassan. It was accomplished in 30 years extending from 1920-1950 and published in four consecutive editions in 1928, 1941 (Persatuan Islam), 1953 and 1956. It strongly advocated the ideas of reform inspired by Muhammad Abduh in Tafsir al-Manar. A. Hassan wrote this lengthy tafsir based on the literal method (harfiyah), that is, word by word translation, except for words that could not be translated in the harfiyah sense, in which case he resorted to their ma‘nawiyah (figurative) meaning. This work adopted the scientific method and emphasized the critical and rational dimension in tafsir, reflecting the foundational framework of exegesis inspired by Abduh and Rida in Tafsir al-Manar.

Tafsir al-Furqan: Kitab al-Furqan fi Tafsir al-Qur’an or al-Furqan Tafsir al-Qur’an is an acclaimed work by A. Hassan. It was accomplished in 30 years extending from 1920-1950 and published in four consecutive editions in 1928, 1941 (Persatuan Islam), 1953 and 1956. It strongly advocated the ideas of reform inspired by Muhammad Abduh in Tafsir al-Manar. A. Hassan wrote this lengthy tafsir based on the literal method (harfiyah), that is, word by word translation, except for words that could not be translated in the harfiyah sense, in which case he resorted to their ma‘nawiyah (figurative) meaning. This work adopted the scientific method and emphasized the critical and rational dimension in tafsir, reflecting the foundational framework of exegesis inspired by Abduh and Rida in Tafsir al-Manar.

Other influential tafsir in the late 19th and early 20th century that were influenced by Tafsir al-Manar includes Tafsir al-Burhan by Haji Abdul Karim Amrullah, Tafsir al-Fatihah by Sayyid Shaykh al-Hadi, Tafsir al-Rawi by Haji Yusuf Rawa, Intisari Tafsir Juzuk ‘Amma by Shaykh Abu Bakar Asha‘ari, Tafsir Pimpinan al-Rahman by Sheikh Abdullah Basmeih and Tafsir al-Misbah by Dr. H. M. Quraish Shihab. Tafsir al-Misbah is the 30-volume work of Prof. Dr. H. M. Quraish Shihab that was principally designed around the framework of Tafsir al-Manar. Shihab had critically analysed Tafsir al-Manar in his works Rasionalitas Al-Qur’an: Studi Kritis Tafsir al-Manar (Qur’anic Rationality: Critical Study of Tafsir al-Manar) and Tafsir al-Manar: Keistimewaan dan Kelemahannya (Tafsir al-Manar: Its Excellence and Deficiency) and explained Abduh’s method of tafsir in his foreword to the translation of Kitab Tafsir Juz ‘Amma by Muhammad Abduh [43]. He strongly upheld the principle of “al-Muhafazah ‘ala al-Qadim al-Salih wa Akhdhu bi al-Jadid al-Aslah (keeping the old and good, and adding the new and better) [38].

Bibliography

- Adams, Charles C., 1968. Islam and Modernism in Egypt: A Study of the Modern Reform Movement Inaugurated by Muhammad ‘Abduh (New York: Russell & Russell).

- Affandi, Bisri, 1976. Shaykh Ahmad al-Surkati: His Role in al-Irshad Movement in Java in the Early Twentieth Century. Master of Arts, Department of Islamic Studies, McGill University.

- Afaf Lutfi al-Sayyid, 1968. Egypt and Cromer: A Study in Anglo-Egyptian Relationship. London: Murray.

- Ahmad Farouk Musa, 2012. Wacana Pemikiran Reformis. Kuala Lumpur: Islamic Renaissance Front.

- Ahmed Ibrahim Abushouk, 2001. A Sudanese scholar in the Diaspora: Ahmad Muhammad al- Surkitti his Life and Career in Indonesia, 1911- 1943. Studia Islamika, 8 (1): 55-86.

- Ahmed Ibrahim Abushouk, 2009. Al-Manar and the Hadhrami Elite in the Malay-Indonesian World: Challenge and Response. In Ahmed Ibrahim Abushouk and Hassan Ahmed Ibrahim (Eds.). The Hadhrami Diaspora in Southeast Asia: Identity Maintenance or Assimilation? Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV.

- Ahmad Murad Merican, 2006. Telling Tales, Print and the Extension of Media: Malay Media Studies Beginning with Abdullah Munsyi Through Syed Shaykh al-Hady and Mahathir Mohamad, Kajian Malaysia. 24 (1-2): 151-169.

- Albert Hourani, 1962. Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age 1789-1939. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Assad Nimer Busool, 1976. Shaykh Muhammad Rashid Rida’s Relations with Jamal al-Din al- Afghani and Muhammad ‘Abduh. The Muslim World, 66 (4): 272-286.

- Azyumardi Azra, 2004. The Origins of Islamic Reformism in Southeast Asia: Networks of Malay- Indonesian and Middle Eastern ‘Ulama’ in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

- Azyumardi Azra, 2006. The Transmission of al-Manar’s Reformism to the Malay-Indonesian world: the Case of al-Imam and al-Munir. In Stephane A. Dudoignon, Komatsu Hisao and Kosugi Yasushi (Eds.). Intellectuals in the Modern Islamic World: Transmission, Transformation and Communication. London & New York: Routledge.

- Bluhm-Warn, Jutta, 1983. A Preliminary Statement on the Dialogue Established between the Reform Magazine Al-Manar and the Malayo-Indonesian World. In Indonesia Circle, pp: 35-42.

- Bluhm-Warn, Jutta, 1997. Al-Manar and Ahmad Soorkattie. Links in the Chain of Transmission of Muhammad ‘Abduh’s Ideas to the Malay-Speaking World. In Peter G. Riddell and Tony Street, Eds., Islam: Essays on Scripture, Thought and Society, Leiden: Brill.

- Deliar Noer, 1973. The Modernist Muslim Movement in Indonesia 1900-1942. London and Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

- Farish A. Noor, Yoginder Sikand and Martin Van Bruinessen, (Eds.). The Madrasa in Asia: Political Activism and Transnational Linkages. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Guillaume Frédérich Pijper, 1984. Beberapa Studi tentang Sejarah Islam di Indonesia 1900-1950, tr. Dr. Tudjimah and Drs. Yessy Dagusdin. Jakarta: Universitas Indonesia.

- Gibb, H.A.R., 1947. Modern Trends in Islam. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Giora Eliraz, 2002. The Islamic Reformist Movement in the Malayo-Indonesian World in the First Four Decades of the Twentieth Century: Insights Gained from a Comparative Look at Egypt. Studia Islamika, 9 (2): 47-87.

- George McTurnan Kahin, 1952. Nationalism and Revolution in Indonesia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Hafiz Zakariya, 2007. From Cairo to the Straits Settlements: Modern Salafiyyah Reformist Ideas in Malay Peninsula. Intellectual Discourse, 15 (2): 125-146.

- Hafiz Zakariya, 2009. Sayyid Shaykh Ahmad al- Hadi’s Contributions to Islamic Reformism in Malaya. In Ahmed Ibrahim Abushouk, Hassan Ahmed Ibrahim (Eds.). The Hadhrami Diaspora in Southeast Asia: Identity Maintenance or Assimilation? Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV.

- Hafiz Zakariya, 2011. Cairo and the Printing Press as the Modes in the Dissemination of Muhammad ‘Abduh’s Reformism to Colonial Malaya. 2nd International Conference on Humanities, Historical and Social Sciences. IPEDR, 17, IACSIT Press, Singapore.

- Hafiz Zakariya, 2006. Islamic Reform in Colonial Malaya: Shaykh Tahir Jalaluddin and Sayyid Shaykh al-Hadi. Ph.d Thesis, University of California, Santa Barbara.

- Hamid, I., 1985. Peradaban Melayu dan Islam. Petaling Jaya: Fajar Bakti Publication.

- Hamka, K.H.A. Dahlan, 1952. In Encyclopaedi Islam Indonesia. Orang-Orang Besar Islam di Dalam dan di Luar Indonesia. Jakarta: Sinar Pujangga.

- Hamka, 1958. Pengaruh Muhammad Abduh di Indonesia. The Influence of Muhammad Abduh in Indonesia. Pidato diucapkan sewaktu menerima gelar Doktor Honoris Causa di Universitas al- Azhar, Mesir. Keynote address delivered in the inaugural lecture of acceptance the Honorary Doctorate from al-Azhar Univeristy, Cairo. Jakarta: Tintamas.

- Hamka, 1967. Tafsir al-Azhar. Jakarta: P.T. Pembimbing Masa.

- Hamka, 1967. Ajahku. Jakarta: Djajamurni.

- Harun Nasution, 1968. The Place of Reason in ‘Abduh’s Theology: Its Impact on his Theological System and Views. Ph.d Thesis, Institute of Islamic Studies, McGill University, Montreal.

- Henry Benda, 1970. Southeast Asian Islam in the Twentieth Century. In P.M. Holt et al. (Ed.). The Cambridge History of Islam, London: Cambridge University Press, Vol: 2. Howard, M. Federspiel, 2001. Islam and Ideology in the Emerging Indonesia State, Leiden: Brill NV.

- Howard, M. Federspiel, 2009. Persatuan Islam: Islamic Reform in Twentieth Century Indonesia. Singapore: Equinox Publishing.

- Ibn ‘Ashur, Muhammad al-Fadil and al-Tafsir wa- Rijaluhu, 1966. Tunis: Dar al-Kutub al-Sharqiyya.

- Ibrahim Abu Bakar, 1994. Islamic Modernism in Malaya: The Life and Thought of Syed Syekh al- Hadi. Kuala Lumpur: Universiti Malaya Press.

- Jajat Burhanuddin, 2004. The Fragmentation of Religious Authority: Islamic Print Media in Early 20th Century in Studia Islamika, vol: 11/1.

- Jajat Burhanudin, 2005. Aspiring for Islamic Reform: Southeast Asian Requests for Fatwas in Al-Manar. Islamic Law and Society, 12(1): 9-26.

- John O. Voll, 1982. Islam: Continuity and Change in the Modern World. Boulder, Co: Westview Press.

- Abdullah, M., S. Arifin and K. Ahmad, 2012. The influence of Egyptian Reformists and its impact on the development of the literature of Qur’anic exegesis manuscripts in the Malay Archipelago. Arts and Social Sciences Journal, Vol: 52.

- Michael Laffan, 2004. An Indonesian Community in Cairo: Continuity and Change in a Cosmopolitan Islamic Milieu. Indonesia, 77: 1-26.

- Mohamed Aboulkhir Zaki, 1965. Modern Muslim Thought in Egypt and its Impact on Islam in Malaya. (Ph.d Thesis, University of London.

- Mohammad Redzuan Othman, 2005. Egypt’s Religious and Intellectual Influence on Malay Society. KATHA-Journal of the Centre for Civilizational Dialogue, 1: 1-18.

- Mohd Shuhaimi Ishak, 2007. Islamic Rationalism: A Critical Evaluation of Harun Nasution’s Thought. Ph.d Thesis in Usuluddin and Islamic Thought, Kulliyyah of Islamic Revealed Knowledge and Human Sciences, International Islamic University Malaysia.

- Muhammad Abduh and Tafsir Juz ‘Amma, 1999. Translated by Muhammad Bagir. Bandung: Mizan.

- Muhammad Abduh, 2004. Theology of Unity. Translated by Ishaq Musa‘adand Kenneth Cragg. Petaling Jaya: Islamic Book Trust.

- Muhammad Asad, 1980. The Message of the Qur’an. Gibraltar: Dar al-Andalus.

- Muhammady Idris and Kiyai Haji Ahmad Dahlan, 1975. His Life and Thought. M.A. Thesis, Department of Islamic Studies, McGill University, Montreal.

- Muzani, Saiful, 1994. Mu‘tazilah Theology and the Modernization of the Indonesian Muslim Community: An Intellectual Portrait of Harun Nasution. Studia Islamika, Vol: 1 (1).

- Nadzirah Mohd., 2006. Athar Madrasat al-Manar fi al-tafasir al-Malayuwiyah: tafsir al-Qur’an al- hakim li-Shaykh Mustafa ‘Abd al-Rahman Mahmud unmudhajan. Ph.d Thesis, Kulliyyah of Islamic Revealed Knowledge & Heritage and Human Sciences, International Islamic University Malaysia.

- Naseer, H. Aruri, 1977. Nationalism and Religion in the Arab World: Allies of Enemies. The Muslim World, 67 (4): 266-279.

- Natalie N. Mobini-Kesheh, 1996. The Arab Periodicals of the Netherlands East Indies, 1914-1942. In Bijdragen tot de Toal-, Land-en Volkenkunde, Leiden, 152 (2): 236-256.

- Nik Ahmad Nik Hassan, 1963. The Malay Press: The Early Phase of the Malay Vernacular Press, 1867-1906. Journal of the Malaysian Branch Royal Asiatic Society, 36 (201): 37-78.

- Nikki R. Keddie and Sayyid Jamal ad-Din al- Afghani, 1972. A Political Biography. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Rashid Rida, Muhammad and Tarikh al-Ustadh al- Imam Muhammad ‘Abduh, 1931. Egypt: Matba‘ah al-Manar.

- Raden Hajid, Falsafah Pelajaran Kj. H. Ahmad Dahlan, 1954. Yogyakarta: P.B. Muhammadiyah.

- Richard, C. Martin, Mark R. Woodward and Dwi S. Atmaja, 1997. Defenders of Reason in Islam: Mu‘tazilism from Medieval School to Modern Symbol. Oxford: Oneworld Publications.

- Rosnani Hashim, (Ed.). Reclaiming the Conversation: Islamic Intellectual Tradition in the Malay Archipelago. Petaling Jaya: The Other Press.

- Rushdi Hamka, 2001. Hamka: Keperibadian, Sejarah dan Perjuangannya. In Hamka dan Transformasi Sosial di Alam Melayu. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa & Pustaka.

- Seng Huat Tan, 1961. The Life and Time of Syed Sheikh bin Ahmad al-Hadi. B.A. Thesis, University of Singapore.

- Solichin Salam, 1960. Kiyai Haji Ahmad Dahlan. The Indonesian Herald.

- Solichin Salam and K.H. Ahmad Dahlan, 1963. Reformer Islam Indonesia. Jakarta: Jayamurni.

- Syamsuri Ali, 1997. Al-Munir dan Wacana Pembaharuan Pemikiran Islam 1911-1915. (Master Thesis, IAIN Imam Bonjol, Padang.

- Tamar Djaja, 1965. Pustaka Indonesia: Riwajat Hidup Orang-Orang Besar di Tanah Air, jilid 2. Jakarta: Bulan Bintang.

- Taufik Abdullah, 2009. Schools and Politics: The Kaum Muda Movement in West Sumatra (1927- 1933). Singapore: Equinox Publishing.

- Umar Ryad, 2009. A Prelude to Fiqh al-Aqaliyat: Rashid Rida’s Fatwas to Muslims under non- Muslim Rule. In Christiane Timmerman, Johan Leman, Hannelore Roos & Barbara Segaert (Eds.). In-Between Spaces: Christian and Muslim Minorities in Transition in Europe and the Middle East. Brussels: Peter Lang.

- Wan Sabri and Wan Yusof, 1997. Hamka’s “Tafsir al-Azhar: Qur’anic Exegesis as a Mirror of Social Change. Ph.d Thesis, Temple University.

- Wan Suhana Wan Sulong, 2006. Saudara (1928- 1941): Continuity and Change in the Malay Society. Intellectual Discourse, 14 (2): 179-202.

- William R. Roff, 1994. The Origins of Malay Nationalism. USA: Oxford University Press.

- Yunus M., 1960. Sejarah Pendidikan Islam di Indonesia. Djakarta: Pustaka Mahmudiah.

- Yusuf, Milhan, 1995. Hamka’s Method of Interpreting the Legal Verses of the Qur’an: a Study of his Tafsir al-Azhar. M.A. dissertation, Institute of Islamic Studies, McGill.

- Zainal Abidin Ahmad, 1939. A History of Malay Literature: Modern Developments. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol: 17.

- Zainal Abidin B. Ahmad, 1941. Malay Journalism in Malaya. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol: 19 (2).

Dr Ahmad Nabil Amir is Head of Abduh Study Group, Islamic Renaissance Front. He has a PhD in Usuluddin from the University of Malaya. This essay was first published in the Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research 13 (Mathematical Applications in Engineering): 124-138, 2013 ISSN 1990-9233.

Dr Ahmad Nabil Amir is Head of Abduh Study Group, Islamic Renaissance Front. He has a PhD in Usuluddin from the University of Malaya. This essay was first published in the Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research 13 (Mathematical Applications in Engineering): 124-138, 2013 ISSN 1990-9233.