Ahmad N. Amir, Abdi O. Shuriye & Jamal I. Daoud || 3 January 2021

ON PRESS AND JOURNALS

The celebrated journal al-Manar, edited and published by Muhammad Rashid Rida between 1898-1935, had great ramifications and lasting influence in Southeast Asia. The journal remained in publication for almost 37 years in the first half of the twentieth century that marked the beginning of unprecedented reform in the Muslim world led by Rida, as mentioned by Albert Hourani in his canonical work Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age: “Islamic journalism experienced its first zenith in Egypt with the publication of Rida’s journal, as the early leading salafi scholar in the Muslim world. From the time of its foundation, al-Manar became Rida’s life and in it he published his reflections on the spiritual life, explanation of Islamic doctrine, endless polemics, commentary on the Qur’an, fatwas, his thoughts on world politics, etc.” [64]. In his illustrious work al-Tafsir wa Rijaluhu (Qur’anic exegesis and its exegetes), Shaykh Muhammad al-Fadil b. ‘Ashur related the fame of al-Manar and the incredible reputation it accorded to Abduh: “With the beginning of al-Manar’s publication in the year 1315/1898, al-Ustadh al-Imam’s thoughts started to gain prominence and with the expansion of al-Manar those thoughts started expanding and spreading, to the extent that Shaykh Muhammad ‘Abduh’s leadership was institutionalized in fact by the publication of al-Manar. In it were published his articles, reports, fatwas and his attitudes in defending Islam. In it he also answered his opponents and enemies. In it his name was praised and was given the title al-Ustadh al-Imam. In it, the most important consideration of all, al-Manar Qur’anic Commentary was published” (Muhammad al-Fadil b. ‘Ashur, 1966: 196) [9].

The celebrated journal al-Manar, edited and published by Muhammad Rashid Rida between 1898-1935, had great ramifications and lasting influence in Southeast Asia. The journal remained in publication for almost 37 years in the first half of the twentieth century that marked the beginning of unprecedented reform in the Muslim world led by Rida, as mentioned by Albert Hourani in his canonical work Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age: “Islamic journalism experienced its first zenith in Egypt with the publication of Rida’s journal, as the early leading salafi scholar in the Muslim world. From the time of its foundation, al-Manar became Rida’s life and in it he published his reflections on the spiritual life, explanation of Islamic doctrine, endless polemics, commentary on the Qur’an, fatwas, his thoughts on world politics, etc.” [64]. In his illustrious work al-Tafsir wa Rijaluhu (Qur’anic exegesis and its exegetes), Shaykh Muhammad al-Fadil b. ‘Ashur related the fame of al-Manar and the incredible reputation it accorded to Abduh: “With the beginning of al-Manar’s publication in the year 1315/1898, al-Ustadh al-Imam’s thoughts started to gain prominence and with the expansion of al-Manar those thoughts started expanding and spreading, to the extent that Shaykh Muhammad ‘Abduh’s leadership was institutionalized in fact by the publication of al-Manar. In it were published his articles, reports, fatwas and his attitudes in defending Islam. In it he also answered his opponents and enemies. In it his name was praised and was given the title al-Ustadh al-Imam. In it, the most important consideration of all, al-Manar Qur’anic Commentary was published” (Muhammad al-Fadil b. ‘Ashur, 1966: 196) [9].

Al-Manar examined the philosophy of religion, social affairs and civilization (al-‘umran) and was hailed as the main reference for the modern political ideals advanced by Abduh and Rida. The journal promoted the works of Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (1838-1897) and Muhammad Abduh in al-‘Urwa al-Wuthqa, in an attempt to salvage the ummah from its current malaise, fight political tyranny and ignite a revolution against British colonial power. It was published in Paris between March and October 1884 and gained access to Muslim lands through its advocacy of pan-Islamic idealism (al-Ittihad al-Islam or Islamic unity), the critical use of reason and “the reopening of philosophical inquiry to help the condition of Muslims” at the  time. [52]. The philosophy and chief goal of al-‘Urwa al-Wuthqa was “the guidance of man to supremacy on earth as a deputy of God for the establishment of love and justice” [9, 53] and this was perfectly illustrated by Shaykh ‘Afaf Lutfi al-Sayyid in his study of European colonies and modern Egypt: “A Pan-Islamic paper that aimed its message to all the Muslims of the world and urged them to unite and restore the lost glories of Islam, al-‘Urwa was specifically aimed at freeing Egypt from the British occupation. This was to be effected by stirring up public opinion in Egypt and also in India. The ideas expounded in al-‘Urwa may be summarized into two main themes. The first is that true Islam has become corrupted through ignorance and must therefore be reformed – otherwise the Muslims all faced extinction; the second point is that the Muslim countries had been betrayed by their rulers, who, swayed by personal motives of greed and aggrandizement, gave foreigners a free hand in their countries. The consequence was that the Europeans who coveted Muslim lands took advantage of the inner discords of Islam and sought to destroy the religious unity of the Muslim nations.” [3]

time. [52]. The philosophy and chief goal of al-‘Urwa al-Wuthqa was “the guidance of man to supremacy on earth as a deputy of God for the establishment of love and justice” [9, 53] and this was perfectly illustrated by Shaykh ‘Afaf Lutfi al-Sayyid in his study of European colonies and modern Egypt: “A Pan-Islamic paper that aimed its message to all the Muslims of the world and urged them to unite and restore the lost glories of Islam, al-‘Urwa was specifically aimed at freeing Egypt from the British occupation. This was to be effected by stirring up public opinion in Egypt and also in India. The ideas expounded in al-‘Urwa may be summarized into two main themes. The first is that true Islam has become corrupted through ignorance and must therefore be reformed – otherwise the Muslims all faced extinction; the second point is that the Muslim countries had been betrayed by their rulers, who, swayed by personal motives of greed and aggrandizement, gave foreigners a free hand in their countries. The consequence was that the Europeans who coveted Muslim lands took advantage of the inner discords of Islam and sought to destroy the religious unity of the Muslim nations.” [3]

Al-Manar had its ultimate breakthrough through the painstaking effort of al-Hadi, the Khalifa of Kaum Muda [58]. Al-Hadi’s unwavering resolve to reclaim the ideal of Abduh and extend his views had strongly contributed to enhance the pace of reform and renewal, and was instrumental insofar the birth of these “islah-oriented” magazines helped speed up the transmission process of Islamic reformation notions from the Middle East to the Muslim people in the Malay Archipelago region” [38].

The dissemination of Abduh’s reformism ignited a new consciousness in the Malay community who now saw the need to restore the dynamic role of the ummah, reclaim the high position of its civilization and revive its rational and religious sciences. This was idealized with the rise of dynamic Islamic movements such as Muhammadiyah, al-Irshad, Serikat Islam, Jong Islamieten Bond (JIB or Young Muslim Union) and Persatuan Islam, through the publication of islah-oriented press and journals such as al-Imam, al-Munir and Seruan Azhar that promoted reform and a modern interpretation of Islam. The ensuing Pan Islamic ideals revived Abduh’s modern ideas, as documented by Hafiz Zakariya: “Al-Manar also inspired the reformists to publish journals and other writings that promoted parallel reformist agenda in the Malay world” [22]. In projecting a modern Islamic worldview, al-Manar played a crucial role in inaugurating reform and rallying support from the masses, as explicated by Nadzirah Mohd: “Since al-Manar’s existence at the end of the nineteenth century, that school of thought has made a vital contribution that in taking a different direction from the traditional exegesis in its methodology of explicating the Qur’anic verses. Being very concerned about religious, political and social reform, it has made a great impact in changing the worldview of Muslims in general.”[48]

The main ideal advocated in al-Manar is tajdid and islah (renewal and reform) and its impact reverberated throughout the continent, sparking a vibrant and lasting tradition of reform in Southeast Asia. It inspired the publication of many islah-oriented magazines and journals such as Majallat al-Imam (1906-1908), al-Munir (1911-1916), Neracha (1911), Tunas Melayu (1913), Seruan Azhar (1927), Akhbar, Qalam, Pengasoh, al-Ikhwan (1926-1931) and Saudara (1928-1941). This helped promote modern and progressive ideas through a balanced and rational interpretation of Islam.

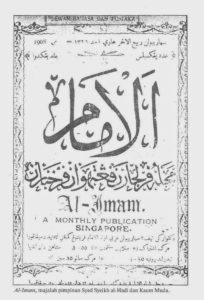

Al-Imam: Al-Imam (The Leader) was founded in Singapore in 1906 by Syeikh Muhammad Tahir Jalaluddin al-Falaki al-Azhari (1869-1956), Muhammad Salim al-Kalali, Muhammad ibn ‘Aqil al- Yahaya (1863-1931), Haji Abbas Muhammad Taha and Sayyid Shaykh al-Hadi (1863-1934). The release of al-Imam “marked the beginning of a new trend and outlook in the contents of the Malay newspapers” [51]. Its pivotal aim was “to disseminate the reformist goals of al-Manar in the Malay language” [40] as professed by Sayyid Muhammad ibn ‘Aqil ibn Yahaya (the co- founder of al-Imam) to Sayid Muhammad Rashid Rida. Al-Imam was released “to revitalize the teachings of Islam in the region and to reintroduce the Islamic concept of life and worship free from heretical innovation and other harmful elements alien to the nature of the religion.” [66]. Its fundamental framework was meaningfully crafted to “to remind those who are forgetful, to awaken those who are asleep and to lead those who have gone astray and to communicate news of hope to them.” [41].

Al-Imam: Al-Imam (The Leader) was founded in Singapore in 1906 by Syeikh Muhammad Tahir Jalaluddin al-Falaki al-Azhari (1869-1956), Muhammad Salim al-Kalali, Muhammad ibn ‘Aqil al- Yahaya (1863-1931), Haji Abbas Muhammad Taha and Sayyid Shaykh al-Hadi (1863-1934). The release of al-Imam “marked the beginning of a new trend and outlook in the contents of the Malay newspapers” [51]. Its pivotal aim was “to disseminate the reformist goals of al-Manar in the Malay language” [40] as professed by Sayyid Muhammad ibn ‘Aqil ibn Yahaya (the co- founder of al-Imam) to Sayid Muhammad Rashid Rida. Al-Imam was released “to revitalize the teachings of Islam in the region and to reintroduce the Islamic concept of life and worship free from heretical innovation and other harmful elements alien to the nature of the religion.” [66]. Its fundamental framework was meaningfully crafted to “to remind those who are forgetful, to awaken those who are asleep and to lead those who have gone astray and to communicate news of hope to them.” [41].

Since its first publication on 23 July 1906 until it ceased to publish in 1908, al-Imam had released 31 issues. In the 12th issue of its publication, it daringly proclaimed that “al-Imam is a mortal enemy of all sorts of bid‘a (unwarranted innovations in religion), superstition, imitations and alien custom that encroaches into religion” (Mohammad Redzuan Othman, 2005: 4). This echoes the ideals and objectives of al-Manar which are “to promote social, religious and economic reforms; to prove the suitability of Islam as a religious system under present conditions and the practicality of the Divine Law as an instrument of government; to remove superstition and belief that do not belong to Islam and to counteract false teachings and interpretations of Muslim beliefs…; to promote general education, together with the reform of text-books and methods of education and to encourage progress in the science and arts; and to arouse the Muslim nations to competition with other nations in all matters which are essential to national progress.” [1]

Al-Imam advocated a progressive and dynamic worldview, and it published works that strongly reflected the ideal and aspiration of al-Manar together with the modern reformist thought that flourished in Europe, as observed by Ahmad Murad Merican: “In imitating the Egyptian reformist journal al-Manar, al-Imam manifests itself as a continuation of the European reformist movement of Martin Luther on the Malay world, centered upon the Enlightenment. In many ways, al-Imam demonstrates the dissemination of values similar to the pamphlet journalism in early-modern Europe” [7].

Al-Manar was widely circulated in Sumatra, Java, Kalimantan and Sulawesi, with working agents in Jakarta, Tjiandur, Surabaya, Semarang, Pontianak, Sambas and Makasar. The journal played a crucial role as “cultural brokers, translating the new purity, rationalism and vitality of Islam into the Malay language – the Archipelago’s lingua franca – and also into terms relevant to a local, Malay-Indonesian frame of reference.” [30]

Al-Imam released substantive articles on tajdid and undertook the rigorous task of translating Abduh’s commentary of the Qur’an and part of Tafsir al-Manar into Malay, as mentioned by Shaykh Tahir Jalaluddin, the editor of Al-Imam, in vol. 3, no. 4 (1908): “As already mentioned in the previous edition of al-Imam we promised to provide our readers with a translation of the Qur’anic commentary in al-Imam, which is derived from the lectures of the late al-Ustadh al-Shaykh Muhammad Abduh at al-Azhar. In order to fulfill our promise, here in this volume we begin by presenting the introduction [of the Qur’anic commentary], which was delivered in a lecture by Muhammad Abduh at al-Azhar in the month of Muharram 1316 H and it was also published in the third volume of al-Manar.” [35].

The journal was published to inspire reform on a grand scale. As stated by Hafiz Zakariya, by “utilizing the available print technology, the reformists promoted their ideas through publications, the most important of which was of al-Imam (1906-1908)” [21]. It was founded on the same model as al-Manar; it strongly promoted its ideology, highlighted its fundamental legacy and defended its idea of reform as established in Egypt, as proclaimed by Prof. Ahmed Ibrahim Abu Shouk in his analysis of the network between hadhrami elites and the intellectual tradition in Cairo: “The close association of these hadhrami figures with the Arabic Middle East manifested in the modeling of al-Imam on the same pattern of the Cairo-based journal al-Manar and in the translation and reprinting of some of its articles and those published in other Cairo daily newspapers” [6]. Its significant position was confirmed by Sayyid Alwi, al-Hadi’s son, who claimed that his father founded al-Imam “to bring social and religious reforms into Malaya along the lines promulgated by his teacher, Shaikh Mohamed Abduh…to purify Islam from malpractices and non-Islamic influences and to eradicate despondency, inertia and the feeling of inferiority which were predominant among the Muslims in Malaya” [51].

The widespread circulation of al-Imam contributed to the awakening of religious consciousness and was instrumental in the rise of Islamic modernism and modern ideology in Malaya. It was recognized as “one of the most important intellectual loci of reformist Muslims in the Malay-Indonesian world” [11]. The journal reprinted several revolutionary works and articles in al-‘Urwa al-Wuthqa and al-Manar that called for social upliftment, political revival and transformation of religious worldview and robust intellectual pursuit, as remarked by William Roff in his groundbreaking analysis of the foundational philosophy of Malay nationalism in The Origins of Malay Nationalism: “It (al-Imam) represented a radical departure in the field of Malay publications, distinguished from its predecessors both in intellectual stature and intensity of purpose and in its attempt to formulate a coherent philosophy of action for a society with the need for rapid social and economic change.”[67].

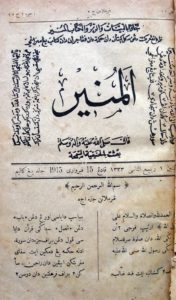

Al-Munir: Al-Munir (Radiating) was published by Haji Abdullah Ahmad, Haji Muhammad Thayeb and Dr Haji Abdul Karim Amrullah (Haji Rasul) in 1911 in Padang Panjang, West Sumatra. Al-Munir propagated the modern idealism of Abduh and strived “to lead and bring Muslim umma to progress based on Islamic injunctions, to nurture peace among nations and human beings and to enlighten the Muslim umma with knowledge and wisdom.” [14] It was released fortnightly and each issue consisted of about sixteen pages printed in the Jawi script. Al-Munir was established rapidly in the whole Sumatera, Java, Sulawesi, Kalimantan and Malaya [27]. The task of al-Munir was to inject dynamism, mobilize reform and instigate a rigorous islah movement. It functioned as the “candle” that illuminated the Muslim ummah in the Dutch East Indies [11] who were severely suppressed and subjugated in their own land. In its discussion of the role of the Islamic journal, al-Munir emphasized that it functioned “like a teacher who gives to its readers guidance in the right path, reminds them of their wrongdoings in the past, consoles those in grief, helps those in suffering from misery, awakens them to virtues and sharpens their reason [11]. This position, as illustrated by Syamsuri Ali, was reminiscent of al-Imam and “is a further indication that al-Munir was eager to continue al-Imam’s mission.” [61]. This is pointed out by Charles C. Adams who argued that “if one takes into account its intellectual genealogy, it was only natural that al-Munir should take over the role of al-Imam in spreading Kaum Muda teachings and opposing all enemies of Islam.” [1].

Al-Munir: Al-Munir (Radiating) was published by Haji Abdullah Ahmad, Haji Muhammad Thayeb and Dr Haji Abdul Karim Amrullah (Haji Rasul) in 1911 in Padang Panjang, West Sumatra. Al-Munir propagated the modern idealism of Abduh and strived “to lead and bring Muslim umma to progress based on Islamic injunctions, to nurture peace among nations and human beings and to enlighten the Muslim umma with knowledge and wisdom.” [14] It was released fortnightly and each issue consisted of about sixteen pages printed in the Jawi script. Al-Munir was established rapidly in the whole Sumatera, Java, Sulawesi, Kalimantan and Malaya [27]. The task of al-Munir was to inject dynamism, mobilize reform and instigate a rigorous islah movement. It functioned as the “candle” that illuminated the Muslim ummah in the Dutch East Indies [11] who were severely suppressed and subjugated in their own land. In its discussion of the role of the Islamic journal, al-Munir emphasized that it functioned “like a teacher who gives to its readers guidance in the right path, reminds them of their wrongdoings in the past, consoles those in grief, helps those in suffering from misery, awakens them to virtues and sharpens their reason [11]. This position, as illustrated by Syamsuri Ali, was reminiscent of al-Imam and “is a further indication that al-Munir was eager to continue al-Imam’s mission.” [61]. This is pointed out by Charles C. Adams who argued that “if one takes into account its intellectual genealogy, it was only natural that al-Munir should take over the role of al-Imam in spreading Kaum Muda teachings and opposing all enemies of Islam.” [1].

From its first edition, al-Munir proclaimed itself as “a journal of Islamic religion, knowledge and information” (Majalah Islam, Pengetahuan dan Perkhabaran). It openly discussed issues considered taboo by Kaum Tua, such as the wearing of neckties and hats and taking photographs, which it defended as never having been forbidden in the Qur’an and hadith. It also insisted that Friday khutba (sermon before Juma‘ah prayer) could be delivered in a language that was understood by the congregation; that Muslims should not follow blindly the classical legal schools (madhhab); and that the Shafi‘i school of law is not the only valid interpretation of Islamic precept and jurisprudence.

Al-Munir also accorded special consideration and high importance to Islamic organizations as a means for “channeling the spirit of reform, encouraging enterprising, vigour, enhancing the nobility of knowledge (kemuliaan ilmu) and cultivating brotherhood of mankind and nations” [11].

Al-Munir‘s struggle for reform met with a heavy backlash from its rivals and dissenters; its position was challenged by conservative ulamas (the so-called Kaum Tua) and some unidentified troublemakers (tukang kacau) who launched the criticisms, on the grounds that “preaching by means of a journal was a western innovation and adopting the western way was bid‘a.” [11, 62]. The journal was discontinued in 1916 after its printing house was burned down.

Saudara: In 1928, Sayid Shaykh al-Hadi published tri-weekly newspaper Saudara (Brethren) that addressed contemporary issues, criticized the traditional, conservative and decadent lifestyle of Malay Muslims, and advocated Islamization and advancement of Malay society [6]. Its aim was to “call for unity and cooperation based on the right path, strengthening Islamic brotherhood, helping each other as advocated by Islam and preaching the Qur’an in order to achieve worldly progress as enjoined by Islam.” [66]. In the first issue, Saudara proclaimed its “intention to initiate a debate”, stressing that “all arising debates would stay within the confines of the law, would not violate the rights of any individual and would be truly sincere.” [66]. This radical work was described by Za‘ba as “a powerful and uncompromising critic of Malay life and a strong advocate of social and religious reformism for Muslims.” [71]

The tradition of reform was furthered by other substantive modernist works such as Seruan Azhar that played a significant role in imparting the idea of reform to Malay folks and peasants. It was first published in 1927 in Jawi Malay script by the Jami‘yyah al- Khairiyah (The Benevolent Society) that aimed to reinforce modern ideas and awaken Islamic consciousness. With the arrival of the reformist wave, many islah-oriented journals and newspapers were published to promote Islamic reformist ideas in Malaya. These included Neracha (1911-1915), Tunas Melayu (1913) and al-Ikhwan (1926-1931) by al-Hadi’s publishing house, Jelutong Press, in Penang [6]. Neracha was published in Singapore and edited by Haji Abbas b. Mohd Taha; it was released three times a month and consisted of four pages of articles culled from Turkish, Egyptian and other foreign newspapers [66].

The tradition of reform was furthered by other substantive modernist works such as Seruan Azhar that played a significant role in imparting the idea of reform to Malay folks and peasants. It was first published in 1927 in Jawi Malay script by the Jami‘yyah al- Khairiyah (The Benevolent Society) that aimed to reinforce modern ideas and awaken Islamic consciousness. With the arrival of the reformist wave, many islah-oriented journals and newspapers were published to promote Islamic reformist ideas in Malaya. These included Neracha (1911-1915), Tunas Melayu (1913) and al-Ikhwan (1926-1931) by al-Hadi’s publishing house, Jelutong Press, in Penang [6]. Neracha was published in Singapore and edited by Haji Abbas b. Mohd Taha; it was released three times a month and consisted of four pages of articles culled from Turkish, Egyptian and other foreign newspapers [66].

Al-Ikhwan was first published on 16 September, 1926 as an important medium through which al-Hadi conveyed his ideas to the Muslim people in Malaya. Its main objective was to serve as a forum and “an arena of competition for writers enabling them to give their contribution to the public by guiding them to the right path” (Al-Ikhwan 1, no. 1, 1926:1) [66]. In a special column of al-Ikhwan, al-Hadi “published stirring articles on the need of purifying Islam, on the progress of more advanced Muslim countries, on their staggering reforms and modernization and on the elasticity of Islam for adjustment to modern conditions.” [70].

Bibliography

- Adams, Charles C., 1968. Islam and Modernism in Egypt: A Study of the Modern Reform Movement Inaugurated by Muhammad ‘Abduh (New York: Russell & Russell).

- Affandi, Bisri, 1976. Shaykh Ahmad al-Surkati: His Role in al-Irshad Movement in Java in the Early Twentieth Century. Master of Arts, Department of Islamic Studies, McGill University.

- Afaf Lutfi al-Sayyid, 1968. Egypt and Cromer: A Study in Anglo-Egyptian Relationship. London: Murray.

- Ahmad Farouk Musa, 2012. Wacana Pemikiran Reformis. Kuala Lumpur: Islamic Renaissance Front.

- Ahmed Ibrahim Abushouk, 2001. A Sudanese scholar in the Diaspora: Ahmad Muhammad al- Surkitti his Life and Career in Indonesia, 1911- 1943. Studia Islamika, 8 (1): 55-86.

- Ahmed Ibrahim Abushouk, 2009. Al-Manar and the Hadhrami Elite in the Malay-Indonesian World: Challenge and Response. In Ahmed Ibrahim Abushouk and Hassan Ahmed Ibrahim (Eds.). The Hadhrami Diaspora in Southeast Asia: Identity Maintenance or Assimilation? Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV.

- Ahmad Murad Merican, 2006. Telling Tales, Print and the Extension of Media: Malay Media Studies Beginning with Abdullah Munsyi Through Syed Shaykh al-Hady and Mahathir Mohamad, Kajian Malaysia. 24 (1-2): 151-169.

- Albert Hourani, 1962. Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age 1789-1939. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Assad Nimer Busool, 1976. Shaykh Muhammad Rashid Rida’s Relations with Jamal al-Din al- Afghani and Muhammad ‘Abduh. The Muslim World, 66 (4): 272-286.

- Azyumardi Azra, 2004. The Origins of Islamic Reformism in Southeast Asia: Networks of Malay- Indonesian and Middle Eastern ‘Ulama’ in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

- Azyumardi Azra, 2006. The Transmission of al-Manar’s Reformism to the Malay-Indonesian world: the Case of al-Imam and al-Munir. In Stephane A. Dudoignon, Komatsu Hisao and Kosugi Yasushi (Eds.). Intellectuals in the Modern Islamic World: Transmission, Transformation and Communication. London & New York: Routledge.

- Bluhm-Warn, Jutta, 1983. A Preliminary Statement on the Dialogue Established between the Reform Magazine Al-Manar and the Malayo-Indonesian World. In Indonesia Circle, pp: 35-42.

- Bluhm-Warn, Jutta, 1997. Al-Manar and Ahmad Soorkattie. Links in the Chain of Transmission of Muhammad ‘Abduh’s Ideas to the Malay-Speaking World. In Peter G. Riddell and Tony Street, Eds., Islam: Essays on Scripture, Thought and Society, Leiden: Brill.

- Deliar Noer, 1973. The Modernist Muslim Movement in Indonesia 1900-1942. London and Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

- Farish A. Noor, Yoginder Sikand and Martin Van Bruinessen, (Eds.). The Madrasa in Asia: Political Activism and Transnational Linkages. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Guillaume Frédérich Pijper, 1984. Beberapa Studi tentang Sejarah Islam di Indonesia 1900-1950, tr. Dr. Tudjimah and Drs. Yessy Dagusdin. Jakarta: Universitas Indonesia.

- Gibb, H.A.R., 1947. Modern Trends in Islam. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Giora Eliraz, 2002. The Islamic Reformist Movement in the Malayo-Indonesian World in the First Four Decades of the Twentieth Century: Insights Gained from a Comparative Look at Egypt. Studia Islamika, 9 (2): 47-87.

- George McTurnan Kahin, 1952. Nationalism and Revolution in Indonesia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Hafiz Zakariya, 2007. From Cairo to the Straits Settlements: Modern Salafiyyah Reformist Ideas in Malay Peninsula. Intellectual Discourse, 15 (2): 125-146.

- Hafiz Zakariya, 2009. Sayyid Shaykh Ahmad al- Hadi’s Contributions to Islamic Reformism in Malaya. In Ahmed Ibrahim Abushouk, Hassan Ahmed Ibrahim (Eds.). The Hadhrami Diaspora in Southeast Asia: Identity Maintenance or Assimilation? Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV.

- Hafiz Zakariya, 2011. Cairo and the Printing Press as the Modes in the Dissemination of Muhammad ‘Abduh’s Reformism to Colonial Malaya. 2nd International Conference on Humanities, Historical and Social Sciences. IPEDR, 17, IACSIT Press, Singapore.

- Hafiz Zakariya, 2006. Islamic Reform in Colonial Malaya: Shaykh Tahir Jalaluddin and Sayyid Shaykh al-Hadi. Ph.d Thesis, University of California, Santa Barbara.

- Hamid, I., 1985. Peradaban Melayu dan Islam. Petaling Jaya: Fajar Bakti Publication.

- Hamka, K.H.A. Dahlan, 1952. In Encyclopaedi Islam Indonesia. Orang-Orang Besar Islam di Dalam dan di Luar Indonesia. Jakarta: Sinar Pujangga.

- Hamka, 1958. Pengaruh Muhammad Abduh di Indonesia. The Influence of Muhammad Abduh in Indonesia. Pidato diucapkan sewaktu menerima gelar Doktor Honoris Causa di Universitas al- Azhar, Mesir. Keynote address delivered in the inaugural lecture of acceptance the Honorary Doctorate from al-Azhar Univeristy, Cairo. Jakarta: Tintamas.

- Hamka, 1967. Tafsir al-Azhar. Jakarta: P.T. Pembimbing Masa.

- Hamka, 1967. Ajahku. Jakarta: Djajamurni.

- Harun Nasution, 1968. The Place of Reason in ‘Abduh’s Theology: Its Impact on his Theological System and Views. Ph.d Thesis, Institute of Islamic Studies, McGill University, Montreal.

- Henry Benda, 1970. Southeast Asian Islam in the Twentieth Century. In P.M. Holt et al. (Ed.). The Cambridge History of Islam, London: Cambridge University Press, Vol: 2. Howard, M. Federspiel, 2001. Islam and Ideology in the Emerging Indonesia State, Leiden: Brill NV.

- Howard, M. Federspiel, 2009. Persatuan Islam: Islamic Reform in Twentieth Century Indonesia. Singapore: Equinox Publishing.

- Ibn ‘Ashur, Muhammad al-Fadil and al-Tafsir wa- Rijaluhu, 1966. Tunis: Dar al-Kutub al-Sharqiyya.

- Ibrahim Abu Bakar, 1994. Islamic Modernism in Malaya: The Life and Thought of Syed Syekh al- Hadi. Kuala Lumpur: Universiti Malaya Press.

- Jajat Burhanuddin, 2004. The Fragmentation of Religious Authority: Islamic Print Media in Early 20th Century in Studia Islamika, vol: 11/1.

- Jajat Burhanudin, 2005. Aspiring for Islamic Reform: Southeast Asian Requests for Fatwas in Al-Manar. Islamic Law and Society, 12 (1): 9-26.

- John O. Voll, 1982. Islam: Continuity and Change in the Modern World. Boulder, Co: Westview Press.

- Abdullah, M., S. Arifin and K. Ahmad, 2012. The influence of Egyptian Reformists and its impact on the development of the literature of Qur’anic exegesis manuscripts in the Malay Archipelago. Arts and Social Sciences Journal, Vol: 52.

- Michael Laffan, 2004. An Indonesian Community in Cairo: Continuity and Change in a Cosmopolitan Islamic Milieu. Indonesia, 77: 1-26.

- Mohamed Aboulkhir Zaki, 1965. Modern Muslim Thought in Egypt and its Impact on Islam in Malaya. (Ph.d Thesis, University of London.

- Mohammad Redzuan Othman, 2005. Egypt’s Religious and Intellectual Influence on Malay Society. KATHA-Journal of the Centre for Civilizational Dialogue, 1: 1-18.

- Mohd Shuhaimi Ishak, 2007. Islamic Rationalism: A Critical Evaluation of Harun Nasution’s Thought. Ph.d Thesis in Usuluddin and Islamic Thought, Kulliyyah of Islamic Revealed Knowledge and Human Sciences, International Islamic University Malaysia.

- Muhammad Abduh and Tafsir Juz ‘Amma, 1999. Translated by Muhammad Bagir. Bandung: Mizan.

- Muhammad Abduh, 2004. Theology of Unity. Translated by Ishaq Musa‘adand Kenneth Cragg. Petaling Jaya: Islamic Book Trust.

- Muhammad Asad, 1980. The Message of the Qur’an. Gibraltar: Dar al-Andalus.

- Muhammady Idris and Kiyai Haji Ahmad Dahlan, 1975. His Life and Thought. M.A. Thesis, Department of Islamic Studies, McGill University, Montreal.

- Muzani, Saiful, 1994. Mu‘tazilah Theology and the Modernization of the Indonesian Muslim Community: An Intellectual Portrait of Harun Nasution. Studia Islamika, Vol: 1 (1).

- Nadzirah Mohd., 2006. Athar Madrasat al-Manar fi al-tafasir al-Malayuwiyah: tafsir al-Qur’an al- hakim li-Shaykh Mustafa ‘Abd al-Rahman Mahmud unmudhajan. Ph.d Thesis, Kulliyyah of Islamic Revealed Knowledge & Heritage and Human Sciences, International Islamic University Malaysia.

- Naseer, H. Aruri, 1977. Nationalism and Religion in the Arab World: Allies of Enemies. The Muslim World, 67 (4): 266-279.

- Natalie N. Mobini-Kesheh, 1996. The Arab Periodicals of the Netherlands East Indies, 1914-1942. In Bijdragen tot de Toal-, Land-en Volkenkunde, Leiden, 152 (2): 236-256.

- Nik Ahmad Nik Hassan, 1963. The Malay Press: The Early Phase of the Malay Vernacular Press, 1867-1906. Journal of the Malaysian Branch Royal Asiatic Society, 36 (201): 37-78.

- Nikki R. Keddie and Sayyid Jamal ad-Din al- Afghani, 1972. A Political Biography. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Rashid Rida, Muhammad and Tarikh al-Ustadh al- Imam Muhammad ‘Abduh, 1931. Egypt: Matba‘ah al-Manar.

- Raden Hajid, Falsafah Pelajaran Kj. H. Ahmad Dahlan, 1954. Yogyakarta: P.B. Muhammadiyah.

- Richard, C. Martin, Mark R. Woodward and Dwi S. Atmaja, 1997. Defenders of Reason in Islam: Mu‘tazilism from Medieval School to Modern Symbol. Oxford: Oneworld Publications.

- Rosnani Hashim, (Ed.). Reclaiming the Conversation: Islamic Intellectual Tradition in the Malay Archipelago. Petaling Jaya: The Other Press.

- Rushdi Hamka, 2001. Hamka: Keperibadian, Sejarah dan Perjuangannya. In Hamka dan Transformasi Sosial di Alam Melayu. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa & Pustaka.

- Seng Huat Tan, 1961. The Life and Time of Syed Sheikh bin Ahmad al-Hadi. B.A. Thesis, University of Singapore.

- Solichin Salam, 1960. Kiyai Haji Ahmad Dahlan. The Indonesian Herald.

- Solichin Salam and K.H. Ahmad Dahlan, 1963. Reformer Islam Indonesia. Jakarta: Jayamurni.

- Syamsuri Ali, 1997. Al-Munir dan Wacana Pembaharuan Pemikiran Islam 1911-1915. (Master Thesis, IAIN Imam Bonjol, Padang.

- Tamar Djaja, 1965. Pustaka Indonesia: Riwajat Hidup Orang-Orang Besar di Tanah Air, jilid 2. Jakarta: Bulan Bintang.

- Taufik Abdullah, 2009. Schools and Politics: The Kaum Muda Movement in West Sumatra (1927- 1933). Singapore: Equinox Publishing.

- Umar Ryad, 2009. A Prelude to Fiqh al-Aqaliyat: Rashid Rida’s Fatwas to Muslims under non- Muslim Rule. In Christiane Timmerman, Johan Leman, Hannelore Roos & Barbara Segaert (Eds.). In-Between Spaces: Christian and Muslim Minorities in Transition in Europe and the Middle East. Brussels: Peter Lang.

- Wan Sabri and Wan Yusof, 1997. Hamka’s “Tafsir al-Azhar: Qur’anic Exegesis as a Mirror of Social Change. Ph.d Thesis, Temple University.

- Wan Suhana Wan Sulong, 2006. Saudara (1928- 1941): Continuity and Change in the Malay Society. Intellectual Discourse, 14 (2): 179-202.

- William R. Roff, 1994. The Origins of Malay Nationalism. USA: Oxford University Press.

- Yunus M., 1960. Sejarah Pendidikan Islam di Indonesia. Djakarta: Pustaka Mahmudiah.

- Yusuf, Milhan, 1995. Hamka’s Method of Interpreting the Legal Verses of the Qur’an: a Study of his Tafsir al-Azhar. M.A. dissertation, Institute of Islamic Studies, McGill.

- Zainal Abidin Ahmad, 1939. A History of Malay Literature: Modern Developments. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol: 17.

- Zainal Abidin B. Ahmad, 1941. Malay Journalism in Malaya. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol: 19 (2).

Dr Ahmad Nabil Amir is Head of Abduh Study Group, Islamic Renaissance Front. He has a PhD in Usuluddin from the University of Malaya. This essay was first published in the Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research 13 (Mathematical Applications in Engineering): 124-138, 2013 ISSN 1990-9233.

Dr Ahmad Nabil Amir is Head of Abduh Study Group, Islamic Renaissance Front. He has a PhD in Usuluddin from the University of Malaya. This essay was first published in the Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research 13 (Mathematical Applications in Engineering): 124-138, 2013 ISSN 1990-9233.