Osman Softić || 7 April 2022

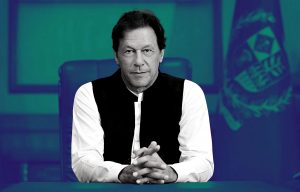

Pakistan has become embroiled in a deep political crisis which culminated late last week, prompting Pakistani president Arifur Rahman Alvi to dissolve parliament, thus circumventing the vote of no confidence motion in the government of prime minister Imran Khan. It is now widely believed that had the vote been permitted to take place the Khan government could have fallen. The decision by the speaker of the ruling Pakistani Tehreek-e-Insaf, Pakistan Justice Movement (PTI) to adjourn the parliamentary session before a no-confidence motion against the government, is viewed by critics as a desperate attempt by the prime minister to cling to power at all costs. There has been a widely spread disaffection across Pakistan over the government’s poor performance in managing the economy and foreign affairs. Some observers assess the latest Pakistani political turmoil as an unprecedented constitutional crisis that may trigger far-reaching consequences. Overt military dictatorship, democratic parliamentarism often underwritten by disproportionate influence of the army behind the scenes, as Pakistan’s ultimate arbiter and arguably the most powerful political force in the country, have intermingled throughout modern history of Pakistan from its formation in 1947 until present day.

Pakistan has become embroiled in a deep political crisis which culminated late last week, prompting Pakistani president Arifur Rahman Alvi to dissolve parliament, thus circumventing the vote of no confidence motion in the government of prime minister Imran Khan. It is now widely believed that had the vote been permitted to take place the Khan government could have fallen. The decision by the speaker of the ruling Pakistani Tehreek-e-Insaf, Pakistan Justice Movement (PTI) to adjourn the parliamentary session before a no-confidence motion against the government, is viewed by critics as a desperate attempt by the prime minister to cling to power at all costs. There has been a widely spread disaffection across Pakistan over the government’s poor performance in managing the economy and foreign affairs. Some observers assess the latest Pakistani political turmoil as an unprecedented constitutional crisis that may trigger far-reaching consequences. Overt military dictatorship, democratic parliamentarism often underwritten by disproportionate influence of the army behind the scenes, as Pakistan’s ultimate arbiter and arguably the most powerful political force in the country, have intermingled throughout modern history of Pakistan from its formation in 1947 until present day.

The Prime Minister claims that the attempt at a no confidence vote against him was unconstitutional and that it violated article 5 of the Pakistani constitution. Khan’s supporters are adamant that the Pakistani opposition has been used as a convenient tool of Washington whose “puppet masters” decided to no longer tolerate an independent foreign policy course of Pakistan. Once a fiercely loyal ally of the United States, Islamabad has been steadily pivoting to Beijing and most recently even to Moscow, a cold war adversary of Pakistan. It is worth recalling that China pledged to invest $70 billion in Pakistan’s largest infrastructure project, China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). This infrastructure megaproject symbolizes the backbone of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a complex network of highways, railways, gas and oil pipelines stretching along Pakistan from north to south. Gwadar port on the Arabian sea represents the most strategic core of the entire project and has become a cause for controversies prompting local opposition by Balochi people who feel marginalized due to privileged contracts apparently being given to Chinese corporations and labor. Baluchistan harbors a protracted insurgency separatist movement whose destabilizing attacks undermine CPEC and slow down China’s New Silk Road initiative, which some observers attribute to a secret meddling of India’s RAW intelligence operatives. CPEC stretches from China’s western border in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous region (XUAR) and as such signifies a lifeline as an alternative corridor between China and Africa, Middle East and Europe. This corridor shortens the time and reduces the cost of the sea route that needs to pass through the Malacca Straits, a narrow passage between Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore, which in the event of any future serious US-China conflict could be blocked and China made isolated from its trading partners in the world. Such a scenario would bring Chinese industry to its knees. Pakistan is therefore China’s most valuable strategic partner. In addition to the CPEC, in Pakistan, a similar project, albeit of smaller scale and importance, is being built by China to reach the Bay of Bengal via Myanmar (Burma). This is known as the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) project. Large gas reserves are located in the coastal area of Myanmar’s Rakhine province (Arakan), where for more than a decade we have witnessed a genocide against the Muslim minority Rohingya, who had lived in the area for centuries and from which they were expelled. CMEC, a secondary energy-trade corridor through which China seeks to ensure its long-term strategic independence from a possible US blockade, stretches from Kunming in the Chinese province of Yunnan, through Myanmar all the way down to the port of Kyaukphyu. Interestingly, just a hundred kilometers to the south, the deep-sea Port of Sittwe is built by India with its investments as part of its strategic energy solutions in the Bay of Bengal region so that it can draw on the rich resources of Myanmar, designed to also prevent Beijing’s monopolization of the region. These two ports in Myanmar, China and India are counting on as the two major competing powers in the region are practically a mirror of the ports of Gwadar in Pakistan and Chabahar in Iran, which are also strategic energy veins on which China and India rely, trying to advance their respective their geo economic and geostrategic interests in South Asia, a pivotal region where more than half of the world’s population lives. As tectonic shifts are taking place and economic and strategic interests rapidly pivot from west to east this part of the world is increasingly becoming of paramount importance for the future of global relations between major word powers. Hence the increased interest of Washington and its allies for this part of the world. Washington has been on a diplomatic offensive in South Asia for some time now. Former US president Barack Obama visited Myanmar (Burma) as well as his Secretary of State Hilary Clinton trying to lure this resource rich Asian dictatorship into American camp by propping up the hybrid semi democratic regime of Aung San Suu Kyi in the past to encircle China with a US friendly regime in order to block China’s intrusion into the Bay of Bengal. Turbulent developments in Myanmar which brought back military dictatorship last year confirms the failure of American policy to achieve its goals.

Altering foreign policy trajectory of Pakistan, especially if it could destabilize Pakistan-China relations and slow the progress of BRI would certainly serve the interest of global American hegemony. Due to India’s irreplaceable role in this process as India is tremendously important for a successful US policy in the Indo-Pacific, Washington seems eager to spare India from its criticism despite of India’s draconian human rights violations of Muslims in Kashmir and looking the other way before explicit BJP’s fascist policies towards its Muslims, Christians and other minorities. Washington appears to be even content with Indie’s continuation of a close strategic partnership with Russia, despite Russian aggression on Ukraine. India is of great strategic importance to Washington in implementing the latest Indo-Pacific strategy and New Delhi is fully aware of this. India therefore feels free to unscrupulously pursue its internal policy of exclusivity based on racist Hindu ideology, in order to create a Hindu state of Hindu Rashtra. The Biden administration, which boasts a policy of protecting human rights, including the rights of religious and ethnic minorities, a policy it has placed at the core of its foreign policy strategy, is quite agile when it comes to condemning human rights violations in China (Uighurs in Xinjiang, Tibet, Inner Mongolia , Taiwan, Hong Kong), but when it comes to India, its strategic partner in the QUAD regional association, American diplomacy acts in contravention of its proclaimed principles is seen as completely duplicitous. This, in fact, proves how much human rights policy in international relations is conditioned by far more pressing concerns dictated by both realpolitik underpinned by geopolitical reasoning and economic interests which are ultimately aimed at preserving the global hegemonic position of the United States.

Altering foreign policy trajectory of Pakistan, especially if it could destabilize Pakistan-China relations and slow the progress of BRI would certainly serve the interest of global American hegemony. Due to India’s irreplaceable role in this process as India is tremendously important for a successful US policy in the Indo-Pacific, Washington seems eager to spare India from its criticism despite of India’s draconian human rights violations of Muslims in Kashmir and looking the other way before explicit BJP’s fascist policies towards its Muslims, Christians and other minorities. Washington appears to be even content with Indie’s continuation of a close strategic partnership with Russia, despite Russian aggression on Ukraine. India is of great strategic importance to Washington in implementing the latest Indo-Pacific strategy and New Delhi is fully aware of this. India therefore feels free to unscrupulously pursue its internal policy of exclusivity based on racist Hindu ideology, in order to create a Hindu state of Hindu Rashtra. The Biden administration, which boasts a policy of protecting human rights, including the rights of religious and ethnic minorities, a policy it has placed at the core of its foreign policy strategy, is quite agile when it comes to condemning human rights violations in China (Uighurs in Xinjiang, Tibet, Inner Mongolia , Taiwan, Hong Kong), but when it comes to India, its strategic partner in the QUAD regional association, American diplomacy acts in contravention of its proclaimed principles is seen as completely duplicitous. This, in fact, proves how much human rights policy in international relations is conditioned by far more pressing concerns dictated by both realpolitik underpinned by geopolitical reasoning and economic interests which are ultimately aimed at preserving the global hegemonic position of the United States.

The political crisis in Pakistan, in addition to rising prices and economic difficulties facing Pakistanis stems from frustrations over poor economic governance also reflects concerns about the direction Pakistan’s foreign policy course has taken under the Imran Khan leadership. Prime Minister Khan and his allies accuse Washington of trying to overthrow his government while labeling his political opponents as Washington’s vassals who are “carrying out Washington’s order” in an attempt to overthrow his Tehreek-i-Insaf-led government. This is apparently evidenced by the frequent visits of political opposition leaders to the US Embassy in Islamabad in recent days before preparations for a vote of no confidence motion in the Khan government. Imran Khan cites a dispatch from the Pakistani embassy in Washington broadcasting a conversation with a senior State Department official who criticized the prime minister’s recent political moves. Of course, in a diplomatic manner, US officials rejected any insinuations that they were trying to overthrow his government.

Imran Khan’s visit to Moscow, just days before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, has been criticized by the West, especially the United States. Americans, of course, have a huge indirect influence on Pakistan, through their role in the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Negotiations have been under way for some time between the Khan government and International Monetary Fund on a $6 billion aid package that Pakistan desperately needs to rehabilitate the country’s dire social situation as inflation linked to the COVID-19 pandemic and other repercussions over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on rising food and fuel prices, which have inevitably caused dissatisfaction among citizens facing difficult living conditions. Some analysts believe that Prime Minister Khan’s problems began after the public began to perceive that the Pakistani armed forces, in a way, signaled that they no longer supported the prime minister. Pakistani generals are reportedly dissatisfied with his government’s poor economic governance and disapprove of his foreign policy moves. The Pakistani leader openly supported the Taliban’s return to power in Kabul last year. Khan commented on their capture, saying the Afghans had “broken the shackles of slavery”. It is worth bearing in mind that Imran Khan is an ethnic Pashtun, and the Taliban are mostly recruited from the ranks of Pashtuns. There is a possibility that the prime minister is no longer wanted at the helm of the state, among other things, because he is not trusted an ethnic Pashtun.

Pakistan Tehreeki Insaf (PTI) movement arose on a platform to fight Pakistani political dynasties that represent the Pakistani establishment. The armed forces did not respond to the policy of perpetual friction between two major Pakistani feudal corrupt cliques, and in 2018 supported the arrival of the Khan movement to head the government in Islamabad. Pakistan’s two largest opposition parties are traditional feudal organizations or political dynasties. Pakistan’s Muslim League Nawaz (PMLN) led by Shahbaz Sharif, a brother of a former discredited Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, whose stronghold is in the majority province of Punjab. On the other hand, Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), led by Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, the son of a former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto and former President Asif Zardari, has the largest stronghold in Sindh province. These two parties took turns at the political helm of Pakistan for decades, when the army allowed them to do so, and when the army did not have direct power.

Pakistan Tehreeki Insaf (PTI) movement arose on a platform to fight Pakistani political dynasties that represent the Pakistani establishment. The armed forces did not respond to the policy of perpetual friction between two major Pakistani feudal corrupt cliques, and in 2018 supported the arrival of the Khan movement to head the government in Islamabad. Pakistan’s two largest opposition parties are traditional feudal organizations or political dynasties. Pakistan’s Muslim League Nawaz (PMLN) led by Shahbaz Sharif, a brother of a former discredited Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, whose stronghold is in the majority province of Punjab. On the other hand, Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), led by Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, the son of a former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto and former President Asif Zardari, has the largest stronghold in Sindh province. These two parties took turns at the political helm of Pakistan for decades, when the army allowed them to do so, and when the army did not have direct power.

Imran Khan accused these two traditional Pakistani political dynasties of plundering Pakistan’s national wealth and for stashing corruptly acquired wealth into secret accounts abroad in London, Dubai and elsewhere. However, the mentioned two political dynasties, no matter how corrupt, have their supporters and are able to take a large number of their supporters to the streets in show of support. The military dealt with them in its own way, either by wrestling power from them by force or more often by sponsoring counterprotests, usually from influential Islamist groups, which, although politically marginal, are still able to take a large number of supporters to the streets. In recent times, probably with the aim of weakening the Taliban terrorist movement in Pakistan, Tahrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) the military favored some Islamic groups over the others. Two broader Islamic popular trends dominated the Pakistani Islamic stage. The first is based on the tradition of the Deoband Sunni School of Islam and originates from Deoband in India at the time when Pakistan did not exist as a state. This movement is the most widespread among the Pashtuns. The other, rival Islamic movement, originates from a tradition of the Barelvi strain of Islam. The Deobandi trend has adopted some features of Saudi Wahhabism while the Barelvis are more oriented towards the traditionalist Islamic interpretation which also inherits Sufism. It is rooted in the teachings of local Sufi sheikhs and venerates spiritual centers and the cult of Islamic Sufi shrines.

In order to discipline the political elite, the Pakistani military often reaches out, overtly or covertly, to form some kind of tactical alliance with these movements, depending on what seems opportune to it at the time. It is difficult to know for certain whether the military’s signaling that it would not interfere if Pakistani institutions, may have prompted the opposition to confront the government of Prime Minister Khan with full confidence that it will not be curtailed by the generals. Now former Prime minister Khan insists he is fighting for Islam, preserving democracy, and ensuring transparency and justice while arguing that Washington has been trying to overthrow him by interference, meddling and manipulation of the Pakistani opposition.

Pakistani academic Ejaz Akram claims that the American establishment, after being humiliated in Afghanistan and after failing to rally the Islamic world last month to support its leadership in condemning more explicitly Russian invasion of Ukraine and failing to impose sanctions on Russia, after dominating the world, are now entering its terminal hegemonic phase. Washington therefore showed tendencies of an elephant in the porcelain shop, lashing on all sides, rear, front and center. Akram claims that the latest manifestation of such American behavior reflects an attempt to overthrow Imran Khan. This academic calls it an attempt to engineer a regime change in Islamabad, the fact that this was stated by the Prime Minister himself is no small matter. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi also condemned Washington’s interference in the internal affairs of Pakistan, China’s strategic partner. Yi said that Beijing would not allow America to drag smaller nations into conflict, while condemning America’s “Cold War mentality.” China has decided not to allow Washington to hijack from its orbit and a significant Asian partnership in making, comprising Russia, Iran, Afghanistan and some other countries in Central Asia.

Attempts by Pakistani opposition at ousting the Imran Khan government would mean the end of the experiment of a rule in Pakistan by a relatively new political organization that came to power on a platform to fight the establishment steeped in crime, corruption and nepotism. What the Khan government is now asking is for the Pakistani judiciary to investigate whether there has been foreign interference in internal political processes through blackmail and bribery. Imran Khan is still popular with the masses as an embodiment of their aspirations for a better life. On March 27, Imran Khan gave a two-hour speech at a rally of about 200,000 supporters. The prime minister then said publicly that foreign powers were demanding his removal and that the opposition was cooperating with them. At the heart of the crisis is a letter allegedly handed to Pakistan’s ambassador to Washington by a senior State Department official threatening Khan’s government, signaling retaliation if he does not withdraw or change policy, and a vote of no confidence. Khan went a step further and said the next phase of the fight against Pakistan and its independent policies could be an attempt to assassinate him. The government also called on the American ambassador, to whom it sent a demarche, which also speaks of the seriousness of the situation. The very fact that the eminent Pakistani judge Athar Minallah expressed the legal opinion that Prime Minister Khan should not publicly disclose the content of the mentioned document because he took the oath to keep state secrets. All this points to a deep crisis of global proportions, which in some elements is reminiscent of the Ukrainian Maidan 2014. In this case, it is clearly a kind of emergence of a new Cold War between the US and China, over Pakistan’s soil whose territory is becoming a proxy battleground in a new big game taking place between the great powers for supremacy in South Asia.

Akram also states that a session of the state national security council was held, but opposition representatives boycotted the meeting. The meeting decided to address official criticism and condemnation of Washington. It is speculated that the US letter was sent on behalf of the Undersecretary of State through Assad Majeed Khan, Pakistan’s ambassador to America. The letter states that there will be distrust in Khan’s government, that the Prime Minister should be informed that this will happen and that he must not oppose it, but obey it, and in case of any resistance he will face serious consequences. The day after, a no-confidence motion against Prime Minister Imran Khan was launched. Prime Minister Khan reportedly received information from the intelligence community about the modalities used to bribe certain parliamentarians in order to lure them to switch sides. Quite peculiarly, the military leadership declared itself neutral in this political turmoil. The Prime Minister criticized the armed forces, which, as he said, should not remain neutral when it comes to direct interference of foreign powers in Pakistan’s internal political affairs. Akram goes on to say that Foreign Minister Shah Qureshi paid a visit to Beijing on that occasion. After his return from Beijing, allegedly, the army showed understanding for the position of prime minister. Should foreign interference (US intervention) be proven, it could further worsen relations with Washington and Pakistan could face lawsuits that could result in penalties for treason and collaboration with foreign powers to overthrow democratic rule. Opposition leaders could find themselves behind bars. Whether Imran Khan will be able to deal with his opponents in this biggest crisis of his rule to date, whether the armed forces will side with him or against him, will be shown in the coming weeks.

Akram also states that a session of the state national security council was held, but opposition representatives boycotted the meeting. The meeting decided to address official criticism and condemnation of Washington. It is speculated that the US letter was sent on behalf of the Undersecretary of State through Assad Majeed Khan, Pakistan’s ambassador to America. The letter states that there will be distrust in Khan’s government, that the Prime Minister should be informed that this will happen and that he must not oppose it, but obey it, and in case of any resistance he will face serious consequences. The day after, a no-confidence motion against Prime Minister Imran Khan was launched. Prime Minister Khan reportedly received information from the intelligence community about the modalities used to bribe certain parliamentarians in order to lure them to switch sides. Quite peculiarly, the military leadership declared itself neutral in this political turmoil. The Prime Minister criticized the armed forces, which, as he said, should not remain neutral when it comes to direct interference of foreign powers in Pakistan’s internal political affairs. Akram goes on to say that Foreign Minister Shah Qureshi paid a visit to Beijing on that occasion. After his return from Beijing, allegedly, the army showed understanding for the position of prime minister. Should foreign interference (US intervention) be proven, it could further worsen relations with Washington and Pakistan could face lawsuits that could result in penalties for treason and collaboration with foreign powers to overthrow democratic rule. Opposition leaders could find themselves behind bars. Whether Imran Khan will be able to deal with his opponents in this biggest crisis of his rule to date, whether the armed forces will side with him or against him, will be shown in the coming weeks.

Pakistan has been pursuing an independent foreign policy in recent times and under Khan leadership appeared reluctant to obey American dictates. Pakistani citizens are also aware of the tectonic changes that signal the decline of American global power. Ajaz Akram also claims that Pakistanis no longer care about sanctions as before. It is increasingly certain that Pakistan, in cooperation with China, wants to relegate American power and influence outside the region, and that it has the support of Iran, Afghanistan and Russia.The latest constitutional crisis to shake Pakistan increasingly appears to be the battleground between two camps whose protagonists are reportedly the Indo-American Alliance, which uses corrupt political cliques and the media machinery it controls and a group of Westernized liberal intellectuals on the one hand and the democratically elected and legitimate government with a charismatic and popular prime minister supported by the majority of the Pakistani population. What steps will be taken by the Pakistani armed forces will certainly be a decisive factor in the current constellation. Reinstatement or reelection of the PTI to power will largely depend on whether Pakistani generals are able or willing to resist the pressure from its powerful allies in Washington.

Osman Softić is a Research Fellow at the Islamic Renaissance Front. He holds a BA degree in Islamic Studies from the Faculty of Islamic Studies of the University of Sarajevo and has a Master degree in International Relations from the University of New South Wales (UNSW). He contributed commentaries on Middle Eastern and Islamic Affairs for the web portal Al Jazeera Balkans, Online Opinion, Engage and Open Democracy. Osman holds dual Bosnian and Australian citizenship.

Osman Softić is a Research Fellow at the Islamic Renaissance Front. He holds a BA degree in Islamic Studies from the Faculty of Islamic Studies of the University of Sarajevo and has a Master degree in International Relations from the University of New South Wales (UNSW). He contributed commentaries on Middle Eastern and Islamic Affairs for the web portal Al Jazeera Balkans, Online Opinion, Engage and Open Democracy. Osman holds dual Bosnian and Australian citizenship.