Penang Malays: Icons of Reform and Tolerance

Ahmad Fauzi Abdul Hamid | 11 May 2022

The lives of iconic Penang Malays make hugely interesting stories. Vocal, outspoken, occasionally incendiary but always significant, we need to reintroduce them to present and future generations of Malaysians.

The lives of iconic Penang Malays make hugely interesting stories. Vocal, outspoken, occasionally incendiary but always significant, we need to reintroduce them to present and future generations of Malaysians.

Much of the discussion concerning Malays in Penang since Merdeka, spurred by the federally controlled Malay language mainstream media, has focused on their marginalisation. The alleged backwardness of Penang Malays has in fact been trumpeted so often that in the modern Malay imagination, the “Penang Malay” holds the dubious honour of being the rendering of what Malays in general would suffer should they lose control over Malaysia’s politics and economy.

In short, Penang Malays are claimed to have become victims of urbanisation and economic development steered by successive state governments invariably led by non-Malay politicians. To be sure, all of Penang’s chief ministers since independence, irrespective of party affiliation, have been of Chinese descent: Wong Pow Nee, Lim Chong Eu, Koh Tsu Koon and Lim Guan Eng.

Perpetuation of this ethnically skewed narrative, which unduly depicts Malays as victims and non-Malays as de facto oppressors, has lately made its way into racially exclusive social media, in particular WhatsApp groups that chat along ethnocentric lines. When mixed with religious emotions, the narrative can be dangerously inflammatory, such as the baseless rumour that the call for prayer (azan) in Penang had been banned from broadcasting aloud. Most significantly, this narrative neglects the fact that capitalist development is often colour blind, as shown in the eviction at Kampung Buah Pala, where the victims were mostly ethnic Indians.

Most importantly, it also demeans the great contributions that Penang Malays have made to community building and nation building, before and after independence.

A Unique Heritage

In fact, Penang’s Malay community, steered by its colourful history, has made great strides in defending their unique ethno-religious identity and furthering the cause of Islam in a situation where a numerical majority has perennially eluded them. Yet, rather than allowing themselves to be overwhelmed by a sense of being dispossessed like the Palestinians, with whom comparisons have also been made, Penang Malays continue to make vast contributions to Malay society and Malaysian Islam.

In fact, Penang’s Malay community, steered by its colourful history, has made great strides in defending their unique ethno-religious identity and furthering the cause of Islam in a situation where a numerical majority has perennially eluded them. Yet, rather than allowing themselves to be overwhelmed by a sense of being dispossessed like the Palestinians, with whom comparisons have also been made, Penang Malays continue to make vast contributions to Malay society and Malaysian Islam.

Malay sons and daughters of Penang, whether born in the state or immigrants, have indeed exerted a more than peripheral presence within the ranks of Malay luminaries, rendering phenomenal service to Islam in the Malay world and Malaysia as a nation state. In their own way, Penang Malays have become iconic figures well-remembered by those who care to remember, in spite of attempts by the powers-that-be to sideline their contributions whenever they fell out of favour.

In contemporary politics, Penang Malays can be proud of former Prime Minister Tun Abdullah Ahmad Badawi and former Deputy Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim. In the economic sphere, the names of Mydin hypermarket founder Mohamed Ghulam Hussein (d. 2016) and ex-Malaysia Resources Corporation Berhad (MRCB) chairman Abdul Rahman Maidin tower among others as bastions of Malay entrepreneurship. In academia, names like Omar Farouk Bajunid and Ahmad Murad Merican – both now serving the Centre for Policy Research and International Studies (CenPRIS), USM, on a contract basis, are well established in their scholarly disciplines. In arts and culture, everyone knows the late P. Ramlee and composer Ahmad Nawab. In religious activism, Mohd Asri Zainul Abidin and Ahmad Farouk Musa are controversial figures but no less conspicuous in public space. Twice every year during the eve of Aidilfitri and Aidiladha, Muslims will be glued to their television sets watching the announcement of the celebration dates based on the sighting of the new moon made by the Keeper of the Rulers’ Seal, a post now held by Penangite Syed Danial Syed Ahmad, who traces his genealogy to Hijazi sayyids who came to Penang via Aceh.

The list easily goes on. If one wants to do research into it, many more names will appear.

What is palpable from the above listing is that many of the so-called Malays of Penang do not bear traditionally Malay sounding names. Appellations like “Maidin”, “Merican” and “Bajunid” are indicative of their creole heritage – the result of age-old inter-cultural marriages between Malays and itinerant or migrant Arabs and Indians, united by the Islamic faith and symbolised by the terms Arab Peranakan and Jawi Peranakan or Jawi Pekan. “Jawi” has traditionally been used to signify “Malay” while “pekan” means “town”. In colonial Malaya, only Penang and Singapore – both Straits Settlements ruled directly from London – bore the distinction of having Malays who principally resided and plied their trade in towns rather than in kampungs. In spite of their mixed ancestry, these Peranakans identified themselves and were recognised as Malays by virtue of their adoption of the Malay language and Malay customs. While still harbouring emotional attachment to the lands of their forebears such as Hadramaut in Yemen and the coastal regions of southern India, they professed loyalty to Malaya and Malaysia as their new motherland.

The term “Jawi Pekan” was probably coined by British chronicler James Low in the early nineteenth century and immortalised by historian William Roff in his classic work The Origins of Malay Nationalism (1967). These crops of mixed-blood Malays trace their lineage to diverse Arab-Indian groups such as the Sayyids and Sheiks, identifiable by surnames such as “Al-Idrus” and “Al-Aidid”; the Marakkayars, from whom we derive the family name “Merican”; “Labbais”, from which the word “lebai”, i.e. “skullcap” or “one who wears a skullcap”, is derived; and “Rawthers”, a common surname in Penang.

These groups’ advent in Penang must be differentiated from a later wave, beginning in the late nineteenth century and which peaked in the early twentieth century, of Tamil Muslims mainly from Kadayannalur, Tamil Nadu, India, most of whom maintained their Tamil identity – especially the use of Tamil in daily conversation. This latter group of Tamil Muslims – known in local lingo as the mamak community, brought about the popular nasi kandar dish and introduced the iconic “786” symbol on signboards of eateries. Their assimilation into the Malay community through intermarriage has been slower than in the case of the Peranakans, although the imperatives of ethno-religious politics post-independence did raise their urgency to identify themselves as Malays, effected, among other things through activism in Umno.

In motley colonial Penang, Malay was the lingua franca, being the language through which diverse races and linguistic groups including Eurasians, Armenians and Jews could understand one another. As a result of the multifarious interactions, the Malay language in Penang developed a distinctive accent and vocabulary while remaining grounded as a northern Malay dialect. While some researchers perceive the resultant Bahasa Tanjong as a pidgin or contact language that arose out of the multi-layered communication in the marketplace, others locate it within the broad variety of stable Malay dialects that had already taken more than rudimentary form before the arrival of the British.

Indeed, the position of Malay as the language of trade and inter-ethnic communication in maritime South-East Asia had been established by the sixteenth century. English traveller J.T. Thompson for instance recalls in Some glimpse into life in the Far East (1864) his conversation with a Singaporean Jew being in Malay, simply because it was the only language they both understood.

Penang Malays and Reformist Islam: an Unbroken Link

Inducted into a cosmopolitan lifestyle from the very beginning, Penang Malays were hardly affected by the controversy surrounding the identity of Malays of mixed ancestry – whether they deserve to be called pure Malays (Melayu jati) or not, as denoted by the emergence of derogatory terms such as Darah Keturunan Keling (DKK) and Darah Keturunan Arab (DKA). Persaudaraan Sahabat Pena (PASPAM), founded in 1934 by readers of Saudara – the iconic reformist newspaper published by Syed Syeikh al-Hadi (d. 1934) – for instance, had no qualms about accepting Peranakan Malays as members. Al-Hadi, the offspring of an Arab father and a Malay mother and one of the pioneers of the Kaum Muda movement that derived inspiration from the reformist Al-Manar school of Egypt, had purposely relocated from Malacca to Penang in 1918 to take advantage of the latter’s relative openness towards progressive ideas in regenerating the Malay community. In contrast to his futile ventures in Malacca, in Penang al-Hadi successfully founded Madrasah al-Mashoor (1919) and published the newspapers Al-Ikhwan (1926-1928) and Saudara (1928-1940) via his own Jelutong Press, founded in 1928. In his writings, which included an array of novels, al-Hadi demonstrated an anti-colonial yet not bigotedly anti-British streak, more scathingly attacking Malay religio-political elites who had forsaken their community in exchange for worldly pleasures. In his struggle, al-Hadi collaborated closely with Kaum Muda protagonist Syeikh Tahir Jalaluddin (d. 1956), who taught briefly at Madrasah al-Mashoor (1919-1920) and enjoyed professional linkages to the Perak and Johore royalties. Seventy years later in 1989, Syeikh Tahir’s son Hamdan, having completed a distinguished academic career, would assume the post of Governor of Penang in independent Malaysia.

Inducted into a cosmopolitan lifestyle from the very beginning, Penang Malays were hardly affected by the controversy surrounding the identity of Malays of mixed ancestry – whether they deserve to be called pure Malays (Melayu jati) or not, as denoted by the emergence of derogatory terms such as Darah Keturunan Keling (DKK) and Darah Keturunan Arab (DKA). Persaudaraan Sahabat Pena (PASPAM), founded in 1934 by readers of Saudara – the iconic reformist newspaper published by Syed Syeikh al-Hadi (d. 1934) – for instance, had no qualms about accepting Peranakan Malays as members. Al-Hadi, the offspring of an Arab father and a Malay mother and one of the pioneers of the Kaum Muda movement that derived inspiration from the reformist Al-Manar school of Egypt, had purposely relocated from Malacca to Penang in 1918 to take advantage of the latter’s relative openness towards progressive ideas in regenerating the Malay community. In contrast to his futile ventures in Malacca, in Penang al-Hadi successfully founded Madrasah al-Mashoor (1919) and published the newspapers Al-Ikhwan (1926-1928) and Saudara (1928-1940) via his own Jelutong Press, founded in 1928. In his writings, which included an array of novels, al-Hadi demonstrated an anti-colonial yet not bigotedly anti-British streak, more scathingly attacking Malay religio-political elites who had forsaken their community in exchange for worldly pleasures. In his struggle, al-Hadi collaborated closely with Kaum Muda protagonist Syeikh Tahir Jalaluddin (d. 1956), who taught briefly at Madrasah al-Mashoor (1919-1920) and enjoyed professional linkages to the Perak and Johore royalties. Seventy years later in 1989, Syeikh Tahir’s son Hamdan, having completed a distinguished academic career, would assume the post of Governor of Penang in independent Malaysia.

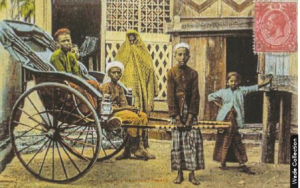

Jawi Pekan children of Tamil background in a rickshaw.

Print culture was undoubtedly an area in which Penang Malays excelled and through which they significantly contributed to the germination of Malay nationalism. Besides al-Hadi's Jelutong Press, Penang had other active printing companies such as Criterion Press, Muhammadiah Press and Persama Press – established by Haji Sulaiman Rawa in Acheen Street in 1930. The inaugural issue of the Jawi Peranakan newspaper published in Singapore in 1876 was actually the initiative of Muhammad Said Dada Muhyiddin who hailed from Gelugor, Penang. The earliest Malay newspapers outside the Straits Settlements, viz. Seri Perak (1893-1895) and Jajahan Melayu (1896-1897) – both printed in Taiping – owed their origins to their chief editor Muhammad Umar Abu Bakar, who hailed from Permatang Sintok, Seberang Perai. Interestingly, while Jawi Peranakan figures patronised Malay dailies in the Jawi or Arabic script, Chinese Peranakans sponsored romanised Malay dailies such as Pemimpin Warita (1895-1897).While most history books identify Islamic reformism and early stirrings of Malay nationalism with the Kaum Muda movement, in Penang both the Kaum Muda and traditionalist scholars broadly categorised as Kaum Tua, had progressive inclinations. Even Haji Muhammad Salleh, a.k.a. Nakhoda Nan Intan, and Datuk Jenaton (derived from the Arabic jannatun, meaning “heaven”) (d. 1789), the Sumatran explorers who founded the earliest Malay settlements in Batu Uban in 1734 and Minden Heights (previously Bukit Jenaton) in 1749 respectively, had embarked on their life-changing voyages to Penang in the wake of their conflicts with adat-based traditionalists in Pagaruyung, Minangkabau.Haji Muhammad Salleh’s younger brother, Ismail or Nakhoda Kechil, was said to have welcomed Francis Light on the shores of Tanjong Penaga – George Town’s precolonial name – upon the latter’s arrival in August 1786. The same Haji Muhammad Salleh is today also remembered in association with Masjid Tengkera in Malacca and with an eponymous mosque beside the grave of Habib Nuh Al-Habsyi in Tanjung Pagar, Singapore.

Centuries later, Penang’s traditionalist scholars such Syeikh Omar Basheer Al-Khalidi (d. 1881) and Syeikh Abdullah Fahim (d. 1961) – Abdullah Badawi’s grandfather – were reformists in many aspects of their thought, and were definitely not the stereotypically insular Kaum Tua type. Syeikh Abdullah Fahim, for instance, maintained cordial relations with al-Hadi, Syeikh Tahir and Syeikh Fadhlullah Suhaimi (d. 1964), who represented traditionalist scholars in a debate with Kaum Muda ideologue Ahmad Hassan Bandung (d. 1958) in 1953 in Penang. Syeikh Fadhlullah’s father, Syeikh Suhaimi (d. 1925), with families based in Singapore and Kelang, also had a Penang wife who unfortunately died upon delivering their stillborn child in 1911. Belying his traditionalist reputation, Syeikh Fadhlullah’s reformist credentials were second to none; both Syeikh Abdullah Fahim and Syeikh Fadhlullah were instrumental in the formation of Parti Islam SeMalaysia (PAS) in Butterworth in 1951.

A boria contingent during the Queen Victoria Diamond Jubilee in 1897.

Conclusion

It is clear from the overview presented above that Malay-Muslims in Penang developed a reformist orientation from their formative stages as a distinctive ethno-religious group whose tolerance of diversity and adoption of multiculturalism had no parallel elsewhere among the states that formed the Malayan Federation that achieved independence in 1957.

It is clear from the overview presented above that Malay-Muslims in Penang developed a reformist orientation from their formative stages as a distinctive ethno-religious group whose tolerance of diversity and adoption of multiculturalism had no parallel elsewhere among the states that formed the Malayan Federation that achieved independence in 1957.

It is no exaggeration to say that tolerance and cosmopolitanism are two traits strongly embedded in the DNA of Penang Malays. Where else do we find in Malaysia a native community, albeit with creole heritage, tolerating for 60 years the leadership of a non-Malay chief minister irrespective of his political affiliation whether or not aligned with the ruling government at federal level?

From an intra-religious perspective, Penang’s experience should be an example for a Muslim world currently plagued by rising sectarianism. Where else, outside of Penang, do we see what originally was a Shi’ite religious festival, i.e. the boria, being passionately adopted by Sunni Muslims and adapted into a cultural artefact of their own? On the flip side, purists would argue that Penang, being separated from the kerajaan culture of other Malay states and its accompanying religious councils, was perhaps overly tolerant such that deviant sects like the Taslim – dubbed by Jakim as the oldest Muslim religious cult in the country, could gain a loyal following in Kampung Seronok, Bayan Lepas. The sect’s legacy still exists in the form of the famous printing company Sinaran Brothers.

Even business outlets linked to the officially banned Darul Arqam organisation continue to flourish in Penang; one can observe with one’s own eyes the string of Global Ikhwan commercial premises in Sungai Ara and Bandar Baru Perda, Bukit Mertajam. Paradoxically, unorthodoxy here translates into business activism rather than into the passivity, dogmatism and militancy of Malaysia’s official Islamic discourse, and is not locked in the shackles of conservatism.

Ahmad Fauzi Abdul Hamid is Professor of Political Science, School of Distance Education, and Consultant Researcher with the Centre for Policy Research and International Studies (CenPRIS), Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), Penang, Malaysia. This essay first appeared at Penang Monthly at http://penangmonthly.com/penang-malays-icons-of-reform-and-tolerance2/

Ahmad Fauzi Abdul Hamid is Professor of Political Science, School of Distance Education, and Consultant Researcher with the Centre for Policy Research and International Studies (CenPRIS), Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), Penang, Malaysia. This essay first appeared at Penang Monthly at http://penangmonthly.com/penang-malays-icons-of-reform-and-tolerance2/