Salbiah Ahmad | 9 August 2016

Abstract: The Qur’an reminds us that God did not decide that all of humanity shall be Muslims. In fact, the Qur’an tells us that we are created males and females, nations and tribes, so that we will know one another (49: 14). We have in our inherited Muslim civilization, notions of rights and responsibilities developed in a particular setting. Seemingly, there are difficulties now in how these messages are to be understood in a multicultural setting. This paper discusses some of the challenges and an enabling framework in engendering good governance and protection of human rights in Malaysia, a multi-cultural Muslim-majority country.

The Knowledgeable Dialogue

In a time of turbulence and uncertainty in some Muslim societies, a preamble in the UNESCO sponsored Universal Declaration of Cultural Diversity, 2001 suggests an assurance of peace as follows:

In a time of turbulence and uncertainty in some Muslim societies, a preamble in the UNESCO sponsored Universal Declaration of Cultural Diversity, 2001 suggests an assurance of peace as follows:

“Affirming that respect for diversity of cultures, tolerance, dialogue and cooperation, in a climate of mutual trust and understanding are among the best guarantees of international peace and security.”

The import of surah Al-Hujurat (49), verse 14 is religious pluralism. Pluralism requires an active engagement with the Other. This requires an understanding of other diverse cultures through knowledgeable dialogue to form a community of citizens, nationally and globally.[1] Peace arises not from a shared belief but from a system of government incorporating the principle of religious pluralism. [2]

The scheme of human rights is a good basis from which to premise the knowledgeable dialogue among communities. Human rights may be defined as universal claims of rights due to all human beings everywhere by virtue of their humanity without distinction on such grounds as race, sex (or gender), religion, language or national origin.[3]

We can and should acknowledge that religious values at their core, provide a positive vision of human interdependence and a compelling motivation for moral responsibility. However, religion is often understood as a system of beliefs or practices, institutions and relationships, that is used by a community of believers to identify and distinguish itself from other communities. It has exclusivity in its identity. This may pose a difficulty in inter-faith conversations when we try to identify values that are applicable across the board, values that have a global appeal that is, universality of values.

For a start, we can explore the three suggested approaches in the sometimes difficult conversations with our communities, to counter exclusivism, in the search for common ground[4]:

- “Religious Inclusivism”: only one religion is correct, but other religions participate in or partially reveal some of the truth of the one correct religion,

- “Religious Pluralism”: ultimately all religions are correct, each offering a different path and partial perspective vis-à-vis the one Ultimate Reality,

- “Henofideism”: One has a faith commitment that one’s religion is correct, while acknowledging that other religions may be correct.

Muslims in these conversations may be reminded of the divinely approved pluralism through a universal morality that touches human beings as members of the human family. The Qur’an emphasises this universalist position in surah Al-Isra, verse 17, which in part reads, “We have honoured (karramna) the children of Adam [with karam, that is, ‘noble nature’]..” It is this noble nature or dignity that distinguishes the human from all other of God’s creatures, a virtue that endows humans with autonomy and responsibility. [5]

Cultural Pluralism and Cultural Legitimacy of Human Rights

The 1993 United Nations World Conference on Human Rights (1993 UN Conference) prompted very rigorous debates on the universality of human rights and cultural relativism. Cultural relativism may be defined as the principle that an individual person’s beliefs and activities should be understood by others in terms of that individual’s own culture.[6] This was reminiscent of the debates to the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). The UDHR was drafted in general terms, which would secure support of member states. The framers avoided identifying religious justifications, but that does not mean that human rights cannot be founded on religious grounds.

The 1993 United Nations World Conference on Human Rights (1993 UN Conference) prompted very rigorous debates on the universality of human rights and cultural relativism. Cultural relativism may be defined as the principle that an individual person’s beliefs and activities should be understood by others in terms of that individual’s own culture.[6] This was reminiscent of the debates to the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). The UDHR was drafted in general terms, which would secure support of member states. The framers avoided identifying religious justifications, but that does not mean that human rights cannot be founded on religious grounds.

Human Rights NGOs in the regional preparatory meeting to the 1993 UN Conference included a clause in the Bangkok NGO Declaration on Human Rights on the importance of “a new understanding of universalism encompassing the richness and wisdom of Asia Pacific countries”.[7] In defending cultural pluralism, the meeting of some 110 NGOs demanded that Asian governments be denied from using the argument of cultural relativism as a shield against accountability of its human rights violations.

The Council of Europe meeting in advance of the 1993 UN Conference adopts the dialogical approach of human rights. In its conclusions, the Council noted that “(m)ore thought and effort must be given to… non-Western religions and cultural traditions. By tracing the linkages between constitutional values… and the concepts, ideas and institutions which are central to Islam or the Hindu-Buddhist tradition or other traditions, the base of support for fundamental rights can be expanded and the claim to universality vindicated. The Western World has no monopoly or patent on basic human rights. We must embrace cultural diversity but not at the expense of universal minimum standards.”[8]

An-Na’im makes the argument for the universal cultural legitimacy of human rights. He maintains that the compliance to a given regime of human rights as a normative system is related to the degree of its legitimacy in the context of the culture(s) where it is supposed to be interpreted and implemented in practice.[9]

In the issue of advancement of Muslim women’s human rights, it has been found necessary to develop a re-reading of the inherited fiqh (principles of Islamic law). This involves the principle in issue, the mainstream methodology of deriving that principle and exploring new methods of re-reading the discrete sources of Islamic law, including fresh exegesis.[10] This is an internal, intra-faith exercise. This process does not displace the Islamic character of the reformed principle nor displace the jurisprudence or the science of deriving a principle of law. The process is culturally legitimate. It would be an uphill task otherwise to expect believing Muslim women and men to accept and implement rights inconsistent with their cultural values and institutions.[11]

In the issue of advancement of Muslim women’s human rights, it has been found necessary to develop a re-reading of the inherited fiqh (principles of Islamic law). This involves the principle in issue, the mainstream methodology of deriving that principle and exploring new methods of re-reading the discrete sources of Islamic law, including fresh exegesis.[10] This is an internal, intra-faith exercise. This process does not displace the Islamic character of the reformed principle nor displace the jurisprudence or the science of deriving a principle of law. The process is culturally legitimate. It would be an uphill task otherwise to expect believing Muslim women and men to accept and implement rights inconsistent with their cultural values and institutions.[11]

State compliance to human rights treaties is voluntary at the international level and States parties generally lack the self-interest to comply with human rights norms in particular. It is primarily up to home grown human rights advocates to engage their communities to pressure their governments to ratify and enforce human rights treaties.

Take the example of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women or CEDAW. Malaysia’s reservations to certain provisions are made on the basis of “Islamic Sharia law and the Federal Constitution”. This would mean that the significant non-Muslim minority population in the country would not have the benefit of the reserved CEDAW provisions through a State party’s blanket imposition of “Islamic Sharia law and the Federal Constitution”. Singapore reportedly a secular state, although her Constitution makes no such claim, has reservations to CEDAW on the basis of “religious or personal law”.

Muslim majority countries with reservations to CEDAW do not explain how and why CEDAW provisions are “culturally illegitimate”. The bottom-up approach of internal transformation would help challenge the status quo and encourage reform to better protect human rights and bring greater state accountability.

The Islamic Commitment to Human Rights

There are detractors in claiming that there is no respect for human rights in Islam. There is however, a growing acceptance of the premise that as human rights are best protected by states within their different cultures and domestic laws, Islam and Islamic law becomes relevant in the effective application of the international regime of human rights in Muslim-majority countries.

El Fadl is of the view that the actual sociopolitical practices in Islamic history has not shown a human rights tradition, but it is possible to eventually construct such a tradition with the requisite amount of intellectual determination, analytical rigour and social commitment.[12] There have been dogmatic approaches by Muslim groups in generating texts on Islamic human rights. The text produced a list of rights purportedly guaranteed by Islam. However these rights are not asserted out of critical engagement with the textual sources in Islam or the historical experience that generated these texts. These lists “were asserted primarily as a means of resisting the deconstructive effects of Westernisation, affirming self-worth, and attaining a measure of emotional empowerment.” [13]

An-Na’im emphasizes that Islamic principles are basically consistent with most human rights norms.[14] Compliance with human rights norms by Muslim states was more likely to be associated with the political, economic, social and cultural conditions of present Islamic societies than Islam itself. However, in the desired transformation of Islamic law or the Shari’a in the present context of Muslim societies, An-Na’im proposes that since any methodology of interpretation is necessarily a human construct, human rights can offer an appropriate framework for human understanding of Islam and the interpretation of the Shari’a.[15]

An-Na’im emphasizes that Islamic principles are basically consistent with most human rights norms.[14] Compliance with human rights norms by Muslim states was more likely to be associated with the political, economic, social and cultural conditions of present Islamic societies than Islam itself. However, in the desired transformation of Islamic law or the Shari’a in the present context of Muslim societies, An-Na’im proposes that since any methodology of interpretation is necessarily a human construct, human rights can offer an appropriate framework for human understanding of Islam and the interpretation of the Shari’a.[15]

One may adopt a varied approach in negotiating the place of Shari’a in the cultural contextual space in Muslim societies or in the Muslim-majority community in terms of tools or strategies with the centering of human rights norms. However as Islam is an identity marker for Muslims, the frame of reference or standard is Islam, and human rights are tools for the interpretation of Shari’a.

There is a synergy and interdependence of pluralism and human rights in these conversations. The more recent human rights conventions in the 21st century such as the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples 2007, reflects the experiences and expectations of other peoples of the world.

The Human Rights Committee to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) [16]in its General Comment 28 addressing Art. 3 ICCPR on equality of rights between men and women took into account, issues of diversity and cultural pluralism. General Comment 28 inter-alia stress that specific regulation of clothing to be worn by women in public may involve a violation of ICCPR-guaranteed rights including article 18 and article 19 “when women are subjected to clothing requirements that are not in keeping with their religion and self-expression; and… article 27, when the clothing requirements conflict with the culture to which the woman can lay a claim.”[17]

The Human Rights Committee to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) [16]in its General Comment 28 addressing Art. 3 ICCPR on equality of rights between men and women took into account, issues of diversity and cultural pluralism. General Comment 28 inter-alia stress that specific regulation of clothing to be worn by women in public may involve a violation of ICCPR-guaranteed rights including article 18 and article 19 “when women are subjected to clothing requirements that are not in keeping with their religion and self-expression; and… article 27, when the clothing requirements conflict with the culture to which the woman can lay a claim.”[17]

In reiteration, the two-fold steps to the knowledgeable dialogue between religion and/or culture, and human rights are:

- The intra-faith dialogue for internal transformation.

- The cross-cultural dialogue.

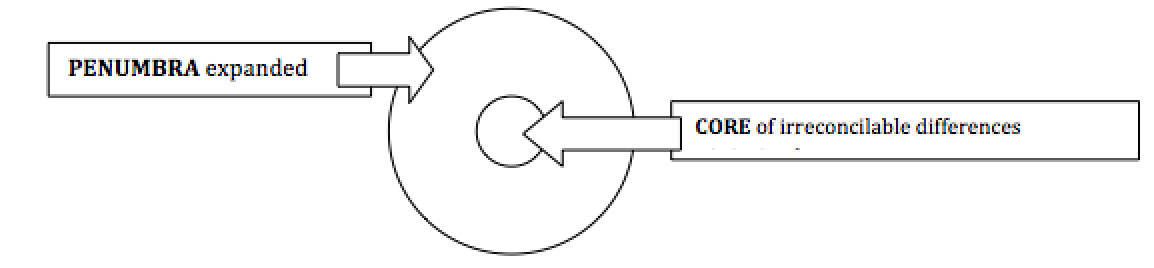

The diagrammatic representation of the synergy and interdependence of human rights and religion through the intra-faith and cross-cultural dialogue is of two concentric circles representing a core and a penumbra.

The function of human rights is to explore the core of irreconcilable differences through these two exchanges to minimize the core and increase the penumbra of shared values or an overlapping consensus.[18]

This dialogical human rights strategy (1) strengthens intercultural recognition of and compliance with core human rights norms, (2) assists human rights initiatives, debates and reforms within cultural traditions, (3) encourages the sustained development of a moral psychology and ethos oriented towards human rights in communities, and (5) puts pressure on state actors to conform to human rights standards and be accountable.[19]

Salbiah Ahmad is a Lawyer by training with LL.B (Honors) University of Singapore and MCL Comparative Law (IIU Malaysia). The author has more than ten years progressive responsible experience on issues of human rights, gender and Islam with regional groups and with the United Nations. This paper is an expansion of her talking points at a roundtable discussion on the topic, on 31 July 2016, organized by the Islamic Renaissance Front in Kuala Lumpur. The guest lecturer was Dr Nader Hashemi, Director of the Centre for Middle East Studies, University of Denver’s Josef Korbel School of International Studies.

Salbiah Ahmad is a Lawyer by training with LL.B (Honors) University of Singapore and MCL Comparative Law (IIU Malaysia). The author has more than ten years progressive responsible experience on issues of human rights, gender and Islam with regional groups and with the United Nations. This paper is an expansion of her talking points at a roundtable discussion on the topic, on 31 July 2016, organized by the Islamic Renaissance Front in Kuala Lumpur. The guest lecturer was Dr Nader Hashemi, Director of the Centre for Middle East Studies, University of Denver’s Josef Korbel School of International Studies.

[1] Abdulaziz Sachedina, The Islamic Roots of Democratic Pluralism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001) pp. 27-36.

[2] ibid. at 44

[3] Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na’im, “The Synergy and Interdependence of Human Rights, Religion and Secularism” in Human Rights and Responsibilities, eds. Joseph Runzo et.al (England: Oneworld Publications, 2003) p.29

[4] Joseph Runzo, “Secular Rights and Religious Responsibilities,” in Human Rights and Responsibilities, eds. Joseph Runzo et.al (England: Oneworld Publications, 2003) p.19

[5] Abdulaziz Sachedina, op.cit. at p. 71.

[6] https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_relativism

[7] A/CONF.157/PC/83. A summary of the NGO Declaration is available at www.internationalhumanrightslexicon.org

[8] Mashood A. Baderin, International Human Rights Law and Islamic Law (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003) p. 5

[9] Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na’im, “State Responsibility to Change Religious and Customary Laws” in Human Rights of Women, ed. Rebecca J. Cook (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1994) p. 171

[10] Amina Wadud in her book, Qur’an and Women (Kuala Lumpur: Fajar Bakti, 1992), develops inter-alia an analytically rigorous hermeneutical exegesis of women’s equality at the time of creation of the first humans in the Qur’an.

[11] Salbiah Ahmad, Striving to Measure Improved Gender Equality and Empowerment of Women in Muslim Societies-CEDAW Legislative Indicators (Bangkok: UNIFEM, Southeast Asia Regional Office, 2009) unpublished.

[12] Khaled Abou El Fadl, “The Human Rights Commitment in Modern Islam”, in Human Rights and Responsibilities, eds. Joseph Runzo et.al (England: Oneworld Publications, 2003) p. 304.

[13] ibid. at p. 306.

[14] An-Na’im’s consistently asserts the gaps in rights of women, non-Muslims and freedom of religion and belief.

[15] Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na’im, Islam and the Secular State: Negotiating the Future of Shari’a (USA: Harvard University Press, 2008) p. 112. An-Na’im explains for the first time, “historical Shari’a” as a product of human reasoning, not divine, immutable or unchangeable in the book, Toward an Islamic Reformation: Civil Liberties, Human Rights, and International Law (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1990). See also Khaled Abou El-Fadl, Speaking in God’s Name: Islamic Law, Authority and Women (Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2001).

[16] The Committee is the body of independent experts that monitors the implementation of the ICCPR by its State parties. See OHCHR site.

[17] General Comment 28 (13) adopted at the 68 session of the Human Rights Committee, OHCHR on 29 March 2000.

[18] Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na’im, (1994) p. 179

[19] John Kelsay and Sumner B. Twiss eds. Religion and Human Rights (New York: The Project on Human Rights, 1994) p. 48-49