Fadlullah Wilmot || 9 May 2022

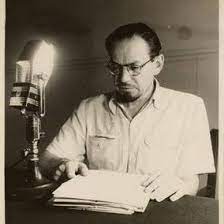

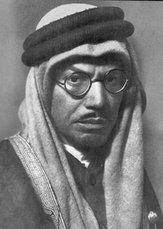

Buried in the small Muslim cemetery in Granada in Spain is one of the most prominent Muslim thinkers of the twentieth century. He was born to a Jewish family on 12 July 1900 in Lviv, then the fourth largest city in the Hapsburg Austro-Hungarian Empire, which was part of the second Polish Republic just before World War II, but is currently within the country in the midst of war, Ukraine. When Leopold Wiess was born, Jews were about one third of the population and Lviv was a major centre of Jewish culture and the Yiddish language. It was the home of the world’s first Yiddish-language daily newspaper, the ‘Lemberger Togblat’.

In September 1926 this young journalist, Leopold Weiss, boarded an underground Berlin train with his wife, Elsa, after a long journey in the Muslim lands, and it was here he was inspired to convert. While travelling in the Berlin subway, he noticed that the people around him had no smiles on their faces as if they were in agony, despite their worldly attainments, well dressed, and well fed. Returning to his flat, a sūra in the Qur’ān he had been reading earlier caught his eyes:

“YOU ARE OBSESSED by greed for more and more. Until you go to your graves. Nay, in time you will come to understand! And once again: Nay, in time you will come to understand! Nay, if you could but understand [it] with an understanding [born] of certainty, you would indeed, most surely, behold the blazing fire [of hell]! In the end you will indeed, most surely, behold it with the eye of certainty: and on that Day you will most surely be called to account for [what you did with] the boon of life!” [Sūra At-Takāthur; 102:1-8]

Leopold said that the Qur’ān literally shook in his hands, he was speechless. He remembered the experience ‘It was an answer: an answer so decisive that all doubt was suddenly at an end. I knew now, beyond any doubt, that it was a God-inspired book I was holding in my hand.’ Muhammad saw at this moment that the Qur’ān had warned the people of the excess of the material in this life would not only lead you to Hellfire but also a life of torment as well. In his own words, he said: ‘This, I saw, was not the mere human wisdom of a distant past in distant Arabia. However wise he may have been, such a man could not by himself have foreseen the torment so peculiar to his twentieth century. Out of the Qur’ān spoke a voice greater than the voice of Muhammad’. He immediately made his way to an Indian Muslim friend living in Berlin and proclaimed the shahada immediately and a few weeks later his wife, Elsa, followed suit. Thus it was that Weiss became a Muslim. Upon conversion, he took the names Muhammad, to honour the Prophet, and Asad – meaning ‘lion” – as a reminder of his given name.

Asad summed up his journey to Islam: “Islam came over to me stealthily like a robber who enters a house at night; but, unlike a robber, it entered to remain for good. What has attracted me to Islam is that great integrated harmonious edifice, which cannot be described. Islam is a complete structure of exquisite workmanship. Each part has been crafted to complete each other. Islam continues -in spite of all the hurdles created by the backwardness of the Muslims – the greatest rising power known to mankind. Hence, I am fully convinced of its revival again.”

But his conversion was not the result of a sudden revelation, it was a journey which had involved his doubts about the teachings of Judaism, his contacts with Muslims in Palestine, his journeys to Egypt, Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, his study of the Qur’an, as well as the turmoil of Europe after the First World War – its moral crisis, the deaths of a whole generation, doubts about old dogmas, the destruction of the war, the economic crisis due to the reparations imposed on Germany. It was also an intellectual journey not only the rejection of greedy materialistic capitalism which had not bought happiness but more importantly the longing for wholeness to reunite what he called “man’s inner and outer beings,” his spiritual and material selves to discover “a life in which man could become one with his destiny and so with himself.

He was indeed a lion for Islam as Muhammad Asad’s life and writings have had a profound impact on the lives of many Muslims all over the world including me during my journey towards Islam and I was really honoured to have met him on his visit to Malaysia arranged by a Malaysian benefactor who had provided him with a home in the final years of his life. Muhammad Asad’s legacy is an inspiration to all Muslims. He lived a life which embodies so many of the virtuous qualities that every Muslim should strive for, no matter their cultural, national, social, or religious background. His search for the truth transported him all around the world, put him in great danger and although his story is a beautiful representation of Islam and its teachings, it also sheds light on the complicated modern history of Muslims in the early twentieth century and the declining condition of the Muslim umma which so frustrated him.

Interestingly, 300 years earlier another famous convert to Islam was born in Lviv — Wojciech Bobowski, who became Ali Ufki. Like Asad, combining his knowledge of both the Islamic-Ottoman and Christian-European cultures, Bobowski helped develop mutual understanding between these different cultures during his lifetime. At the Ottoman court he served as an interpreter, treasurer and musician. He mastered seventeen languages, including – apart from Polish, his native language, and Turkish – Polish, Arabic, Spanish, French, German, Greek, Hebrew, Italian, and Latin. He created of the first ever anthologies of traditional Ottoman music in written form using staff notation. He translated the Bible into Turkish and the Qur’ān into Latin.

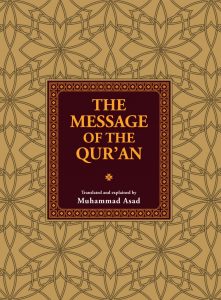

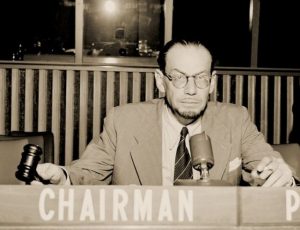

These unpublished letters are connected to some of the events in Muhammad Asad’s amazing life in the period 1935-1986 – mainly his time in India and Pakistan, his marriage, and his time at the United Nations, and his negotiations with his book publishers. His commitment and Islamic principles come out clearly in these letters. “Islam is, as it has always been, the most important factor in my life” he wrote. However, these letters do not cover other parts of his amazing life like the time he spent in Palestine arguing against Zionism or his time in Syria, Afghanistan and Egypt. Nor do they cover the time he spent in Saudi Arabia and Libya where among his friends were Ibn Saud the founder of Saudi Arabia and the Libyan leader Sayyid Ahmad Sanusi and the Libyan freedom fighter, Umar Mukhtar, struggling against brutal Italian colonialism. He was a friend of the Muslim poet-philosopher Muhammad Iqbal, he helped draft the Pakistani constitution, was imprisoned by the British in India as an ‘enemy alien’ during the second world war, in which he lost his father and sister to the Holocaust. Asad became a renowned religious scholar, whose writings on Islam and Muslims span six decades, from the 1920’s to the 1980’s. These include: Unromantisches Morgenland (The Unromantic Orient), 1924; Islam at the Crossroads, 1934; The Road to Mecca, 1954; The Principles of State and Government in Islam, 1961; Sahih al-Bukhāri: The Early Years of Islam, 1935; This Law of Ours and other Essays, 1987, which also included some of his writings from the 1940s. He also brought out a journal, Arafat: A Monthly Critique of Muslim Thought, a monthly periodical founded by him in Kashmir in 1946. His translation and commentary of the Qur’ān that stressed the rationalistic foundation of Islam, The Message of the Qur’ān, was first published in 1980 after 17 years of study.

One review stated: “In its intellectual engagement with the text and in the subtle and profound understanding of the pure classical Arabic of the Qur’ān, Asad’s interpretation is of a power and intelligence without rival in English.” Asad’s dedication in The Message of the Qur’ān reads: Li-qaumin yatafakarun “For people who think”. Muhammad Asad had a special system of translating the Qur’ān into English, which made Islam easier to understand. In the Preface he wrote:

“The Qur’ān cannot be correctly understood if we read it merely in the light of later ideological developments, losing sight of its original purport and the meaning which it had – and was intended to have – for the people who first heard it from the lips of the Prophet himself. For instance, when his contemporaries heard the words Islam and Muslim, they understood them as denoting man’s “self-surrender to God” and “one who surrenders himself to God,” without limiting himself to any specific community or denomination – e.g., in 3:67, where Abraham is spoken of as having “surrendered himself unto God” (kāna musliman), or in 3:52 where the disciples of Jesus say, “Bear thou witness that we have surrendered ourselves unto God (bi-anna musliman).” In Arabic, this original meaning has remained unimpaired, and no Arab scholar has ever become oblivious of the wide connotation of these terms. Not so, however, the non-Arab of our day, believer and non-believer alike: to him, Islam and Muslim usually bear a restricted historically circumscribed significance, and apply exclusively to the followers of the Prophet Muhammad”.

Asad renders kufr and kāfira as ‘denial of the truth’ and ‘one who denies the truth,’ as opposed to the popular translation as ‘disbelief’ and ‘disbeliever’; kitab as ‘divine writ’ or ‘revelation,’ and ahl al-Kitāb as ‘followers of earlier revelation’ as opposed to ‘book’ and ‘people of the book.’ Only “two exceptions from this rule are the terms al-Qur’ān and Sūra, since neither of the two has ever been used in Arabic to denote anything but the title of this particular divine writ and each of its chapter.

Each sūra in the Qur’ān begins with: “Bismillāhi al-rahman al-rahim” except for sura At-Tauba but there were two incidences where this phrase was found in Sūra An-Naml, hence in total they were 114 phrases of Bismillah, equalling the number of sura. It was perhaps the first time that an English translator presented the translation of this verse as, “In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Dispenser of Grace.” This appears to be very close to the words ‘Rahmãn and Rahīm’, while the other English translators of the Qur’ān translate the same verse as:

“In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful.” (Marmaduke Pickthall)

“In the name of Allah, Most Gracious, Most Merciful.” (Abdullah Yusuf Ali)

“In the name of Allah, the Compassionate, the Merciful.”(Ab. Majid Daryabadi)

Similarly, Muhammad Asad translated certain verses of the Qur’ān into English in a manner different from other translations of the Qur’ān.

He translates the verse “inna lladzīna kafaru …” (2:6) as: “Those who are bent on denying the truth …”

While the other English translators of the Qur’ān translate this verse as:

“As for the unbelievers…” (Marmaduke Pickthall)

“As to those who reject faith………” (Abdullah Yusuf Ali)

“Surely those who have disbelieved……..” (Ab. Majid Daryabadi)

This concept appears in Qur’ānic revelation at other places: “…men who have hearts with which they fail to grasp the truth, and eyes with which they fail to see, and ears with which they fail to hear….” (7:179)

According to Asad many misconceptions about the Qur’ān which have been attributed to the verse “Faqtulū anfusakum…” (2:54) are automatically explained if we consider that English translators of the Qur’ān have translated “Faqtulū anfusakum” as:

“Slay one another” (Al-Tabari, Ab. Majid Daryabadi)

“Kill (the guilty) yourselves.”(Muhammad Marmeduke Pickthall)

“Slay yourselves” (Abdullah Yusuf Ali)

But Muhammad Asad translates this as “Mortify yourselves.”

The main aim of Muhammad Asad’s translation was to penetrate the veil that over the years has enveloped the meanings of some Arabic words due to semantic change and to reveal them in their original connotations at the time of the revelation of the Qur’ān. He documented these semantic changes by careful reference to the work of classical lexicographers and philologists and earlier commentators and thus brought a rare freshness and accuracy to his rendering.

Although his grandfather was an Orthodox Rabbi, Leopold’s parents had little religious faith. Even so he was made to spend long hours studying the Jewish scriptures under private tutors which helped in his understanding of the Qur’ān. While he recognised the positive aspects of the moral values of Judaism, Leopard felt the God of the Hebrew Bible and Talmud was “unduly concerned with the ritual by means of which His worshippers were supposed to worship Him” and “strangely preoccupied with the destinies of one particular nation, the Hebrews.” To him, far from being the creator and sustainer of mankind, the God of the Hebrews seemed to be a sort of tribal deity, “adjusting all creation to the requirements of a ‘chosen people.’” His religious studies in fact led him away from Judaism, although “they helped me understand the fundamental purpose of religion as such, whatever its form.” He was no mean linguist as, in addition to his mother tongues of Polish and German, by the time he was 13 he was fluent in Hebrew and Aramaic and, by his mid-twenties, he had mastered English, French, Persian and Arabic.

The family later moved to Vienna. At 14, he escaped school and joined the Austrian army under a false name, but his father found him and took him home. Four years later he was actually drafted in the army, but the Austrian Empire collapsed a few weeks later. He entered at the University of Vienna for degree in art history where his father wanted him get a Ph.D. Leopold had other ideas and wanted to try his hand at journalism. In search of opportunities one summer day, he boarded the train for Prague but later moved to Berlin. After a short stint in film, he did manage to get an entrée into journalism and eventually managed a scoop with an interview with Madame Gorky. So, his journalistic career seemed assured but in 1922, he received a letter which was to change his life forever. His Uncle Dorian, his mother’s youngest brother invited him to Jerusalem. He soon realised that the Jews who were migrating to Palestine were not coming as someone returning to their homeland; but as someone bent on making Palestine into a homeland conceived on European patterns and Europeans aims. He asked Chaim Weizmann, the leader of the Zionist movement and the future president of Israel: How can you ever hope to make Palestine your homeland in the face of the vehement opposition of the Arabs who, after all, are in the majority in this country? ‘We accept that they won’t be in a majority after a few years’, Weizmann ‘answered dryly’.

Leopold became a correspondent for Frankfurter Zeitung visiting Cairo, Amman, then back to Jerusalem and Syria (which then included Lebanon) and Turkey. It was a moment at the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus that he became aware how near the God and the faith were to the Muslims. At the end of 1923 in Vienna, he reconciled with his father. Leopold Weiss had established himself as a writer on Arab and Middle Eastern affair and Frankfurter Zeitung was now willing to remunerate him properly and keen that he returned to the area as soon as he had finished the book he had contracted to write. After finishing the book, Unromantisches Morgenland, in the Spring of 1924, he was off again to the Middle East. For two years Leopold Weiss travelled through Syria, Iraq, Kurdistan, Iran, Afghanistan and Central Asia, and became acquainted with the different forms of Islam while writing some articles as a journalist for the Frankfurter Zeitung

On his second trip Leopold perceived what he saw as a sort of cultural decay at the heart of the Muslim world, especially Islamic scholasticism. ‘Was not the scholastic petrification of this ancient university mirrored, in varying degrees, in the social sterility of the Muslim present? Was not the counterpart of this intellectual stagnation to be found in the passive, almost indolent, acceptance by so many Muslims of the unnecessary poverty in which they lived, of their mute toleration of the many social wrongs to which they were subjected?’ Leopold had noticed these problems in all the Middle-Eastern countries that he visited such as Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Iran Afghanistan.

Despite his appreciation for the teachings of Islam and the Muslims, he remained a non-Muslim during all those years of travel. He recalled that it was in Afghanistan some people he met realised that he had unconsciously become a Muslim. The first was when, one winter day in Afghanistan a man, fixing an iron shoe to his horse said to him: ‘But thou art a Muslim, only thou dost not know it thyself. Why don’t you say now and here: “There is no god but God, and Muhammad is His Prophet” and become a Muslim in fact, as you already are in your heart’. ‘I will go with you tomorrow to Kabul and take you to the amir, and he will receive you with open arms, as one of us’. Leopold travelled on through the Hindu-Kush, in central Afghanistan and for the second time was told that he was Muslim even though he knew it not. A district governor hearing of his passing invited him over for two days to spend in his castle. As recalled by Leopold on the second day, the governor was talking about David and Goliath in a deep state of romanticism about the narrative. ‘The Governor remarked: ‘David was small, but his faith was great.’ Leopold recalling the great contributions of Muslims to world civilisation could not prevent himself from making the comment: ‘And you are many, but your faith is small.’ He said that his host looked at him surprised and feeling embarrassed Leopold tried to explain his comments in a rapid fire of questions:

‘How has it come about that you Muslims have lost your self-confidence — that self-confidence which once enabled you to spread your faith, in less than a hundred years, from Arabia westward as far as the Atlantic and eastward deep into China — and now surrender yourselves so easily, so weakly, to the thoughts and customs of the West? Why can’t you, whose forefathers illumined the world with science and art at a time when Europe lay in deep barbarism and ignorance, summon forth the courage to go back to your own progressive, radiant faith? How is it that Ataturk, that petty masquerade, who denies all value to Islam, has become to you Muslims a symbol of “Muslim revival”?’ Leopold added: ‘Tell me! — how has it come about that the faith of your Prophet and all its clearness and simplicity has been buried beneath a rubble of sterile speculation and the hair-splitting of your scholastics? How has it happened that your princes and great land-owners revel in wealth and luxury while so many of their Muslim brethren subsist in unspeakable poverty and squalor — although your Prophet taught that no one may call himself a faithful who eats his fill while his neighbour remains hungry? Can you make me understand why you have brushed woman into the background of your lives — although the women around the Prophet and his companions took part in so grand a manner in the life of their men? How has it come about that so many of you Muslims are ignorant and so few can even read and write – although your Prophet declared that striving after knowledge is a most sacred duty for every Muslim man and woman and that the superiority of the learned man over the mere pious is like the superiority of the moon when it is full over all other stars?’

Leopold recalled looking at his hosts concerned that his word might have caused offence but to his surprise, however, the governor whispered to him: ‘But you are a Muslim’. Laughing Leopold responded: ‘No, I am not a Muslim, but I have come to see so much beauty in Islam that it makes me sometimes angry to watch you people waste it. Forgive me if I have spoken harshly. I did not speak as an enemy.’ The governor shook his head. ‘No, it is as I have said: you are a Muslim, only you don’t know it yourself’. Although Leopold didn’t convert at that time, in the months that followed, these words would never leave him.

In 1926, he headed home via Marv, Samarkand, Bokhara and Tashkent, across the Turkoman steppes to the Urals and Moscow through what was then the Soviet Union where he witnessed the anti-religious attitudes of the communists towards Muslims. Crossing the Polish frontier, he went direct to Frankfurt and on to Berlin where he delivered a series of lectures at the Academy of Geopolitics. He married Elsa, 41 a widow, whom he had met in Berlin during his previous visit who was on a similar spiritual quest. Often, we would read the Koran together and discuss its ideas; and Elsa, like myself, became more and more impressed by the inner cohesion between its moral teaching and its practical guidance. It was while travelling with Elsa in the subway when he saw that strange phenomenon.

Murad Hofmann, a German diplomat, himself a convert, called him “Europe’s gift to Islam.” This epithet should not be misunderstood to mean that Asad was a western convert attempting to reform Islam. a European intellectual who came to Islam with the aim of liberalizing it. In the words of his son Talal:

“Nothing could be further from the truth. When he embraced Islam (aslama, “submitted,” is the Arabic term) he entered a rich and complex religious tradition that had evolved in diverse ways – mutually compatible as well as in conflict with one another – for over a millennium-and-a-half.”

“In fact most of what my father published in the early years of his life (Islam at the Crossroads, the translation of Sahih al-Bukhari, the periodical Arafat, etc.) was addressed not to Westerners but to fellow-Muslims. I would say, therefore, that he was concerned less with building bridges and more with immersing himself critically in the tradition of Islam that became his tradition, and with encouraging members of his community (Muslims) to adopt an approach that he considered to be its essence. His autobiography was the first publication that was addressed to non-Muslims (as well as to Muslims, of course), a work in which he attempted to lay out to a popular audience, not only how he became a Muslim, but also what he thought was wonderful about Islam“.

Commenting on Asad’s memoir The Road to Mecca Hofmann said, “Perhaps no other book, except the Qur’ān itself has led to a greater number of conversions to Islam.” According to Hoffman Muhammad Asad’s books are the best ones to enable an educated non-Muslim to get a theoretical understanding of Islam. This includes his The Message of the Qur’ān, which in is his precious gift to those interested in religion and spirituality throughout the world.

In the Foreword of his commentary, Muhammad Asad writes that two-things distinguish the Qur’ān from all other religious scriptures: 1. The Qur’ān places more emphasis on reason and invites man to think and reflect in order to believe. 2. According to the Qur’ān, a person’s physical and spiritual life is interconnected, so social and religious life of an individual is inseparable.

There is no contradiction in mundane and spiritual life. Islam is the religion based upon the requirements of human nature which simultaneously takes into account the social, political, intellectual, psychological, spiritual, and other needs of man. The inseparability of physical and spiritual aspects of man have particularly been addressed in the Holy Qur’ān.

Since the intellectual tendency of modern man is mostly towards rational understanding, Muhammad Asad has made a good effort to remove the barriers in the rational and practical understanding of the Qur’ān. Thus, this translation is indispensable for the intellectual class of the society.

The Message of the Qur’ān has set new precedents in the interpretation of the Holy Qur’ān and it still works as a beacon of light for the translators of modern age. In his commentary, he mostly depends upon some noted classical and modern commentators of the Qur’ān like Tabari, Zamakhshāri, Ibn Kathir, Rāzi, Ragheb Isfahāni, Ibn Manzoor, Rashid Rida, Muhammad Abduh and others. In order to reach the most authentic interpretation, he puts special emphasis on etymological and linguistic aspects, he has translated some words and phrases so beautifully that they significantly help to reach the real message of the Qur’ān.

For example, he has translated ‘Taqwa‘ as ‘God consciousness’, ‘Al Kitāb’ as ‘the divine writ’, ‘Kāfir‘ as ‘those who are bent on denying the truth’, and other common “mistranslated’ phrases. By doing so, Muhammad Asad makes an earnest effort to dispel doubts raised by the critics of Islam with rational arguments and scientific reasoning. He reiterates that often the Qur’ān uses parables, allegories and metaphors to express some metaphysical facts and draws the human mind by presenting them in the form of symbols and parables. Given that the metaphysical ideas of religion relate to al-ghayb [a realm which is beyond the reach of human perception], the only way they could be successfully conveyed to us is through loan–images derived from our actual—physical or mental—experiences; or using the words of Zamakhshāri in his commentary on 13:35, “through a parabolic illustration, by means of something which we know from our experience, of something that is beyond the reach of our perception”.

Asad’s interpretive quest, however, is not so much aimed at deciphering al-ghayb, that is, metaphysical subjects such as God’s attributes and the Day of Judgement, as it is to comprehend those passages of the Qur’ān that are expressed in allegorical language about the human condition. For example, the Qur’ān uses metaphors in describing the issue such as the scenes of heaven and hell and according to Muhammad Asad it has been done to draw similar earthly experiences so that they are rightly understood. The Qur’ān tells us clearly that many of its passages and expressions must be understood in an allegorical sense for the simple reason that, being intended for human understanding, they could not have been conveyed to us in any other way. It follows, therefore, that if we were to take every Qur’ānic passage, statement or expression in its outward, literal sense and disregard the possibility of its being an allegory, a metaphor or a parable, we would be offending against the very spirit of the divine writ.

At certain places, he relies more on the interpretations propounded by the modernist Muslim thinkers like Muhammad Abduh and Rashid Rida who place more emphasis on rational understanding. At many places, he tries to rationalize certain metaphysical events (which seem to be against the intellect) which are at times in contrast with the traditional understanding of the Qur’ān. Actually, at many places, he resorts to ‘ijtihad‘ i.e., independent reasoning in the interpretation of the Qur’ānic text.

We have also learned from the history that Muhammad Asad was the intellectual ideologue apart from Muhammad Iqbal, in the formation of the first nation state in the name of Islam, Pakistan. His impact was monumental to the birth of the Islamic nation. Not surprising then when the former Prime Minister of Pakistan, Imran Khan, cites Asad as a motivation that set him on a religious path. However, in respect to Asad’s political thought in his understanding of the Islamic state, his son, Talal, probably has a more nuanced approach:

“It is therefore not entirely clear to me why my father should have endorsed the right of the Islamic state to absolute loyalty, especially since the declaration of faith (shahada) itself specifies absolute loyalty only to God and his Prophet and makes no mention of obedience to earthly rulers or to an earthly organization.”

“But since Qur’anic doctrine insists that everything in the universe is subject to divine sovereignty, how does the state, as a social construct, get its special right to demand absolute loyalty from its subjects? It is precisely because no state can claim divine sovereignty that no spokesperson of an Islamic state can do so. The state may be necessary in our contemporary world for a number of desired functions that only it can perform, and to the extent that it does this in ways considered just and efficient, support from its subjects – as well as from foreigners who live in or visit its territory – will be forthcoming. But the state has no theological title to sovereignty in Islam because unlike Schmitt’s argument that invokes a Christian history, the Islamic state cannot speak as God would speak. It is a creation, not the Creator.”

“Can ethics and religion be brought into public life without their being made subject to sovereignty – and therefore either co-opted by or disruptive of the state? This question was also implicit, I suggest, in my father’s concerns. His preoccupation with ethics is at the bottom of his thinking about the Islamic state. But in my view what he omitted to discuss was the difference between politics and the state.”

“Religion is and has been historically an important source of principled behaviour. It can therefore be suggested that for Muslims the possibilities of political Islam may lie not in its aspiration to acquire state power and to apply state law but in the practice of public argument and persuasion itself – in a struggle guided by deep commitments that are both narrower and wider than the limits of the nation state. Politics in this sense is not a duel between pre-established positions: it is about values in the process of being discovered (or rediscovered) and formed.”

Back to the story, when Asad told his father about his conversion to Islam, he didn’t answer back. His sister told him that his father considered him dead. ‘Thereupon I sent him another letter, assuring him that my acceptance of Islam did not change anything in my attitude toward him or my love for him; that on the contrary, Islam enjoined upon me to love and honour my parents above all other people… But this letter also remained unanswered.’ Muhammad Asad from that point, never saw his father again after this point as he and his wife had left Europe because they could not bear to remain in Europe any longer. What would further Asad’s pain, was the eventual horrific fate that befell on many Jews during that time. In 1942, his father and his sister were deported from Vienna by the Nazis and subsequently died in a concentration camp. He would spend the remaining years as a Muslim in the pursuit of Islamic knowledge which took him all over Arabia. He studied in Medina for five years with knowledgeable scholars in various Islamic sciences.

In 1927, Muhammad Asad made the Hajj pilgrimage and took up residence in the newly formed Kingdom of Saudia Arabia. It was there where he met King Abdul Aziz and would eventually become good friends. Also, on one occasion, Muhammad Asad would carry out a secret mission given to him by King Abdul Aziz. Through his travels and study, he met some of the most prominent Muslim figures of his day such as King Faysal, King Abdullah, King Saud, Muhammad Iqbal, Ahmed Sharif as-Senussi, and his successor Umar Mukhtar. He would journey to the Libyan resistance front against fascist Italian based on requests of The Grand Sanusi, Ahmed Sharif as-Senussi, to deliver information to and from the leader of the rebellion at the time, Umar Mukhtar. After returning to Medina, he relayed the dire situation of the Mujahideen to Ahmed Sharif as-Senussi. He was heartbroken to know that nothing could have been done about Umar Mukhtar’s condition. The following year (1933), The Grand Sanusi had passed away. Later on, Muhammad Asad would travel Easterly towards India and meet one of the most prominent intellectual figures at that time, Muhammad Iqbal. During this time the Muslims in India were suffering from growing tensions between them and the Hindus. Iqbal saw no other solution other than the formation of a Muslim state, the formation of the nation of Pakistan. Muhammad Iqbal persuaded Asad to remain in India and help the Muslims of India establish their separate Muslim state.

After the formation of Pakistan, Asad was afforded citizenship and appointed the Director of the Department of Islamic Reconstruction. After transitioning between different diplomatic roles, he would eventually leave Pakistan to Switzerland then to Spain, Granada, which would become his final home before passing away in 1992 at the age of 92 after giving his lifetime to Islam. He has summed up his journey saying: “Islam is a complete structure of exquisite workmanship. Each part has been crafted to complete each other. Islam continues – in spite of all the hurdles created by the backwardness of the Muslims – the greatest rising power known to mankind. Hence, I am fully convinced of its revival again.” Asad’s disillusionment with the attitude of Muslims towards Islam is evident from the latter part of his work. Muslims did not come up to his expectations. In his book Islam at the Cross Roads, he writes that Muslims have left the way of the Prophet Muhammad (Peace and blessings be upon him) and have started adopting the European culture, regarding Islam as “out-dated” and out of form. This hurt Muhammad Asad.

Upon his demise, in 2008, the entrance square to the UN Office in Vienna was named Muhammad Asad Platz in commemoration of his work and was the first Square in Europe named after a Muslim man. From that moment on, since 2008, that name is intimately connected with the organisation where he used to work as Pakistani Ambassador, but never felt himself limited to the interests of that particular country, and did his best to stand for the interests of all the Muslim world. Indeed, Muhammad Asad’s story is astonishing, to say the least. An Austro-Hungarian-born Jew that went to Arabia and lived with Bedouins, only to become a Muslim. This is all due to one simple desire, the search for truth.

This collection of his letters enables us to get deeper understanding of the chequered life of a man who was a journalist, traveller, writer, linguist, philosopher, political theorist, and diplomat, who has dedicated almost his entire life upon his conversion to Islam, to argue for a rational Islam, to reconcile Islamic teachings with democracy, and to try making the Qur’ān speaks to modern minds. This is a man worth studying and his unpublished letters were beautiful hidden treasures that we stumbled upon.

Fadlullah Wilmot is a Director at Islamic Renaissance Front. He was a regional program manager for the Middle East and Africa for Muslim Aid. He is also former deputy CEO and head of international programs at Islamic Relief Australia. He has served at Universities in Malaysia and Indonesia, and been involved in charitable humanitarian and development work in Southeast Asia, South Asia, Africa and the Middle East.

Fadlullah Wilmot is a Director at Islamic Renaissance Front. He was a regional program manager for the Middle East and Africa for Muslim Aid. He is also former deputy CEO and head of international programs at Islamic Relief Australia. He has served at Universities in Malaysia and Indonesia, and been involved in charitable humanitarian and development work in Southeast Asia, South Asia, Africa and the Middle East.